The Mexican-American War, also known as the War of 1847 or the U.S.-Mexican War, was a pivotal conflict that reshaped the map of North America and left a lasting imprint on both the United States and Mexico. Spanning from April 1846 to February 1848, this war between the United States and Mexico was rooted in territorial disputes and expansionist ambitions, ultimately resulting in the United States acquiring vast swathes of Mexican territory. Often viewed by contemporary critics as an act of American expansionism, the war’s legacy continues to be debated and analyzed today, particularly its impact on the relationship between the two nations and the internal divisions within the United States.

Fueled by the annexation of the Republic of Texas by the U.S. in 1845 and a disagreement over the Texas-Mexico border, the war erupted from a clash of national interests and ideologies. Mexico maintained that Texas’s southern border was the Nueces River, while the United States claimed it extended further south to the Rio Grande. This territorial ambiguity, coupled with the burgeoning American concept of Manifest Destiny, set the stage for a conflict that would dramatically alter the geopolitical landscape.

Seeds of Conflict: Texas Annexation and Border Disputes

Proclamation by President James Polk declaring war with Mexico, 1846

Proclamation by President James Polk declaring war with Mexico, 1846

Proclamation by President James K. Polk announcing the commencement of war against Mexico in 1846, highlighting the official declaration of hostilities.

The annexation of Texas by the United States in 1845 served as the immediate catalyst for the Mexican-American War. Texas had declared its independence from Mexico in 1836, but Mexico refused to recognize its sovereignty and considered it a rebellious province. When the United States, driven by expansionist desires and the concept of Manifest Destiny – the belief that the U.S. was divinely ordained to expand across the continent – annexed Texas, Mexico viewed it as a hostile act and a direct challenge to its territorial integrity.

Adding fuel to the fire was the unresolved border dispute between Texas and Mexico. The Republic of Texas claimed the Rio Grande as its southern and western border, a claim supported by the United States. However, Mexico insisted that the border lay further north at the Nueces River. This contested territory between the two rivers became a flashpoint, with both nations asserting their claims and deploying troops to the region.

In an attempt to resolve these issues diplomatically and further American expansionist goals, U.S. President James K. Polk dispatched John Slidell to Mexico City in September 1845. Slidell’s mission was to negotiate the Texas border, settle outstanding American claims against Mexico, and offer to purchase the territories of New Mexico and California for up to $30 million. However, the Mexican government under President José Joaquín Herrera, already deeply resentful of the Texas annexation and aware of Slidell’s expansionist objectives, refused to receive him. This diplomatic snub further escalated tensions and pushed both nations closer to the brink of war.

“American Blood on American Soil”: The Spark of War

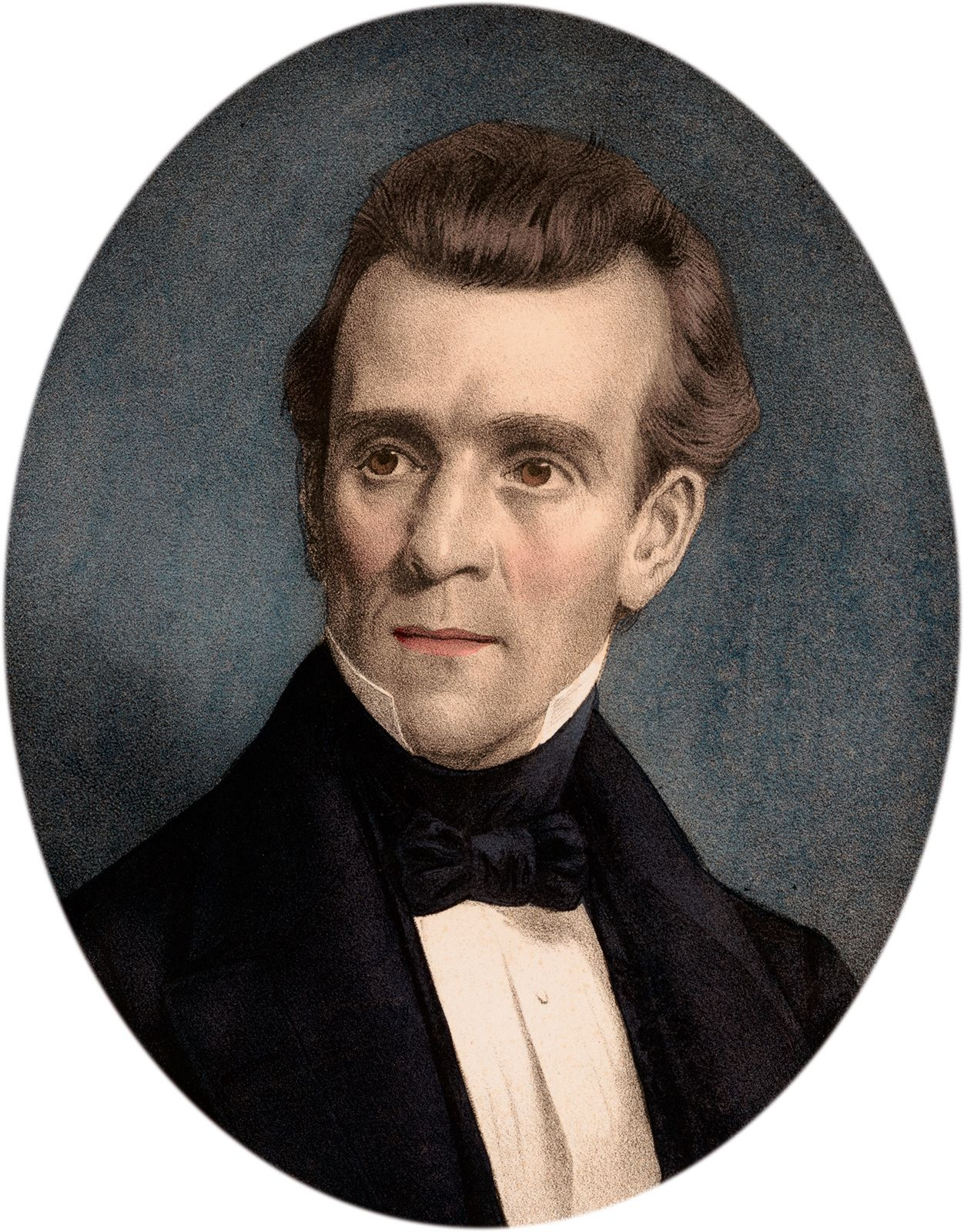

U.S. President James K. Polk, circa 1846

U.S. President James K. Polk, circa 1846

Portrait of James K. Polk, the U.S. President during the Mexican-American War, whose policies and actions were central to the conflict’s outbreak.

Following the rejection of Slidell, President Polk took a more assertive stance. In January 1846, he ordered General Zachary Taylor to move U.S. troops into the disputed territory between the Nueces River and the Rio Grande, effectively occupying land claimed by Mexico. This move was a clear provocation and further inflamed tensions.

On April 25, 1846, Mexican troops crossed the Rio Grande and clashed with Taylor’s forces, resulting in the death or injury of sixteen American soldiers. When news of this skirmish reached Washington D.C., Polk seized the opportunity to rally support for war. On May 11, 1846, he delivered a war message to Congress, famously declaring that Mexico had “invaded our territory and shed American blood on American soil.” This rallying cry, though later contested, successfully galvanized public and political support for a declaration of war.

Domestic Dissension: Opposition to the War in the United States

Lithograph depicting public enthusiasm for the Mexican-American War, 1847

Lithograph depicting public enthusiasm for the Mexican-American War, 1847

“Soldier’s Adieu,” a lithograph from 1847, illustrating the initial wave of public enthusiasm and patriotic fervor in the United States at the onset of the Mexican-American War.

Despite the wave of patriotic fervor that swept through parts of the United States, the Mexican-American War was not without significant domestic opposition. While Democrats, particularly in the South and Southwest, largely supported the war, many Whigs viewed it as an unjust and immoral land grab fueled by expansionist ambitions and the desire to expand slavery.

Within Congress, Whig representatives questioned the legitimacy of Polk’s claims and the justification for war. They challenged the veracity of the assertion that the initial conflict occurred on American soil and debated the President’s authority to unilaterally declare a state of war. The location of the initial skirmish and the validity of Mexico’s claim to the Nueces River border were central points of contention.

One of the most vocal critics of the war was Abraham Lincoln, then a Whig Congressman from Illinois. In December 1847, Lincoln introduced his famous “Spot Resolutions,” demanding that President Polk specify the exact “spot” where American blood was shed and prove that it was indeed on American soil. These resolutions directly challenged Polk’s narrative and sought to hold him accountable for the war’s initiation. Although Lincoln’s resolutions did not pass, they became a powerful symbol of the domestic opposition to the war and highlighted the deep divisions within American society.

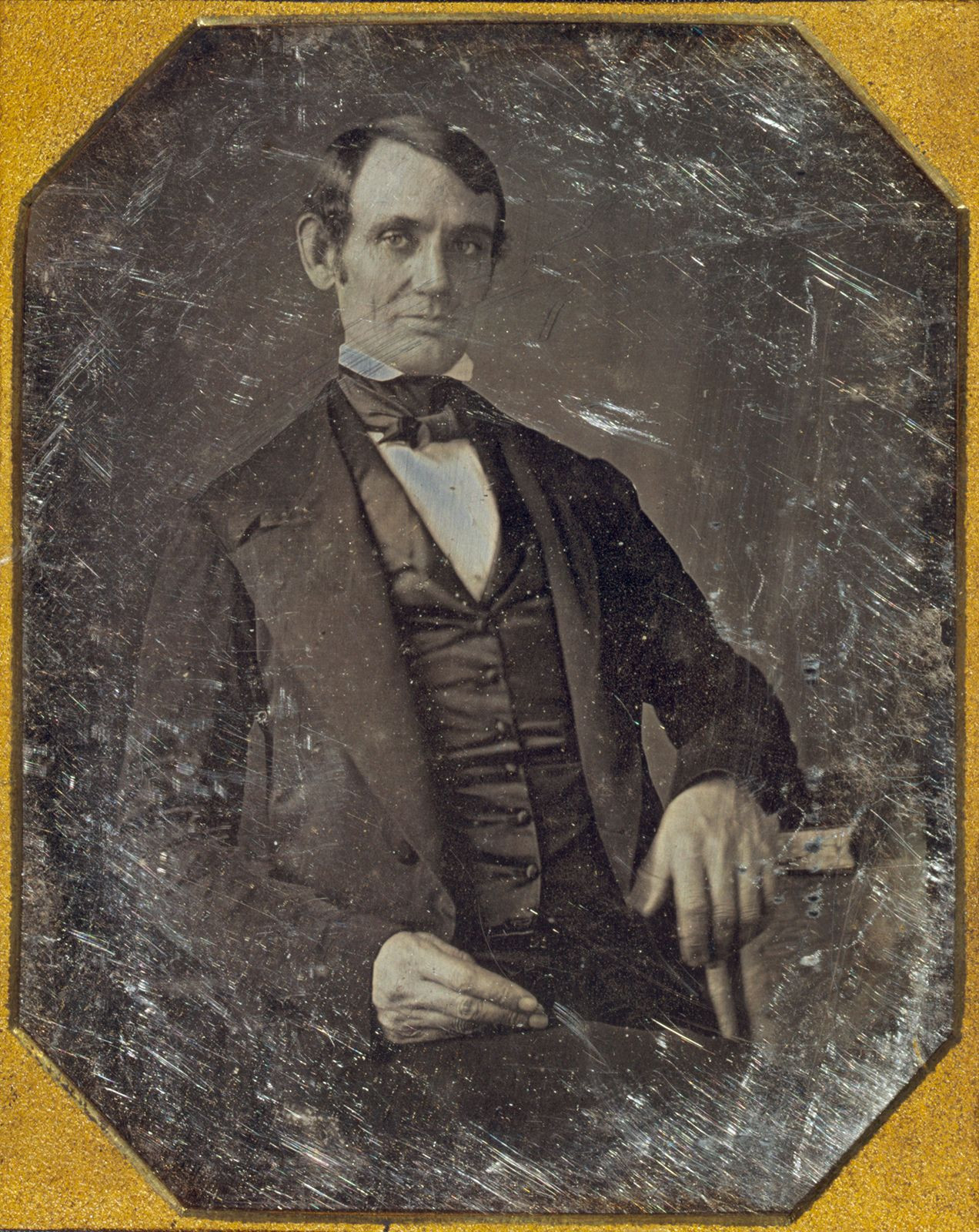

Daguerreotype of Congressman Abraham Lincoln, circa 1846-47

Daguerreotype of Congressman Abraham Lincoln, circa 1846-47

Earliest known photograph of Abraham Lincoln, taken during his term as a Congressman, a period when he voiced strong opposition to the Mexican-American War.

Beyond political opposition, the abolitionist movement also vehemently condemned the war. Abolitionists saw the conflict as a thinly veiled attempt by slave states to expand their territory and increase their political power by creating new slave states out of the Mexican lands. Figures like Henry David Thoreau famously protested the war. Thoreau’s essay Civil Disobedience, born from his brief imprisonment for refusing to pay taxes that he believed would support the war, articulated a powerful moral argument against participating in unjust government actions. He argued that individuals have a moral obligation to resist government policies they deem unjust, even if it means breaking the law.

Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo: Consequences and Legacy

Despite domestic opposition, the United States military, under Generals Zachary Taylor and Winfield Scott, achieved consistent victories throughout the war. American forces invaded and occupied Mexican territory, eventually capturing Mexico City in September 1847. With their capital occupied and facing continued military setbacks, the Mexican government was forced to negotiate peace.

The war officially concluded with the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in February 1848. Under the terms of the treaty, Mexico ceded a vast expanse of territory to the United States, encompassing present-day California, Nevada, Utah, Arizona, New Mexico, and parts of Colorado, Wyoming, Kansas, and Oklahoma. This massive territorial acquisition, known as the Mexican Cession, increased the size of the United States by approximately one-third. In exchange, the United States paid Mexico $15 million and assumed responsibility for American citizens’ claims against the Mexican government.

The Mexican-American War had profound and lasting consequences for both nations. For the United States, it solidified its position as a continental power and fulfilled many of the ambitions of Manifest Destiny. However, the newly acquired territories also reignited the contentious issue of slavery, as debates raged over whether slavery would be permitted in these lands. This sectional conflict over slavery extension ultimately contributed to the escalating tensions that led to the American Civil War.

For Mexico, the war was a national humiliation and a significant territorial loss. It deepened existing political and economic instability and left a legacy of resentment and mistrust towards the United States that would persist for generations. The war remains a significant historical event in Mexico, viewed as a stark example of foreign aggression and the loss of national patrimony.

In conclusion, the Mexican-American War was a watershed moment in the history of both the United States and Mexico. Driven by expansionist ambitions and territorial disputes, the war resulted in a decisive American victory and the acquisition of vast Mexican territories. While it fulfilled American expansionist dreams, it also exacerbated domestic divisions over slavery and left a complex and enduring legacy of political, social, and cultural ramifications for both nations, shaping their relationship for centuries to come.