The Mexican-american War, fought between 1846 and 1848, remains a pivotal yet controversial chapter in the history of both the United States and Mexico. This conflict dramatically reshaped the map of North America, fueled by the expansionist ambitions of the United States and a series of escalating disputes with Mexico. The war concluded with a significant victory for the U.S., resulting in the acquisition of vast territories that now comprise a substantial portion of the American Southwest and Pacific Coast. Understanding the causes, events, and lasting impacts of the Mexican-American War is crucial to grasping the complex relationship between these two nations and the shaping of the modern United States.

Origins of the Conflict: Texas, Manifest Destiny, and Territorial Ambitions

The roots of the Mexican-American War are deeply intertwined with the concept of Manifest Destiny, the belief that the United States was divinely ordained to expand its dominion across the North American continent, stretching from the Atlantic to the Pacific. This ideology gained significant traction in the 19th century, coinciding with American westward expansion and increasing interest in territories held by Mexico, particularly Texas, California, and New Mexico.

The annexation of Texas by the United States in 1845 served as the immediate catalyst for war. Texas had declared and won its independence from Mexico in 1836, but Mexico never formally recognized this independence and considered Texas a rebellious province. When the U.S. annexed Texas, Mexico viewed it as a direct act of aggression and a challenge to its sovereignty. Compounding the issue was a border dispute: the United States claimed the Rio Grande as the southern boundary of Texas, while Mexico insisted on the Nueces River, further north. This disagreement over territory became a central point of contention, providing fertile ground for conflict.

How the Mexican-American War changed the U.S. forever

How the Mexican-American War changed the U.S. forever

Alt Text: Video explaining the transformative impact of the Mexican-American War on the United States.

President James K. Polk, a staunch advocate of Manifest Destiny, actively sought to acquire California and New Mexico from Mexico. He sent diplomat John Slidell to Mexico City to negotiate the purchase of these territories, along with resolving the Texas border dispute and settling outstanding American claims against Mexico. However, the Mexican government, already incensed by the annexation of Texas and wary of further territorial losses, refused to even receive Slidell. This diplomatic deadlock further escalated tensions and pushed both nations closer to war.

Escalation to War: “American Blood on American Soil”

With diplomatic avenues seemingly exhausted, President Polk took a more assertive stance. In January 1846, he ordered U.S. troops under General Zachary Taylor to advance into the disputed territory between the Nueces River and the Rio Grande. This move was deliberately provocative, intended to pressure Mexico into negotiations or, potentially, provoke a military response that could justify further action.

On April 25, 1846, Mexican and American forces clashed north of the Rio Grande. News of this skirmish reached Washington D.C., and Polk seized the opportunity to frame Mexico as the aggressor. In a message to Congress on May 11, 1846, Polk declared that Mexico had “invaded our territory and shed American blood on American soil.” This powerful rhetoric, while contested by some, effectively galvanized public and political support for war.

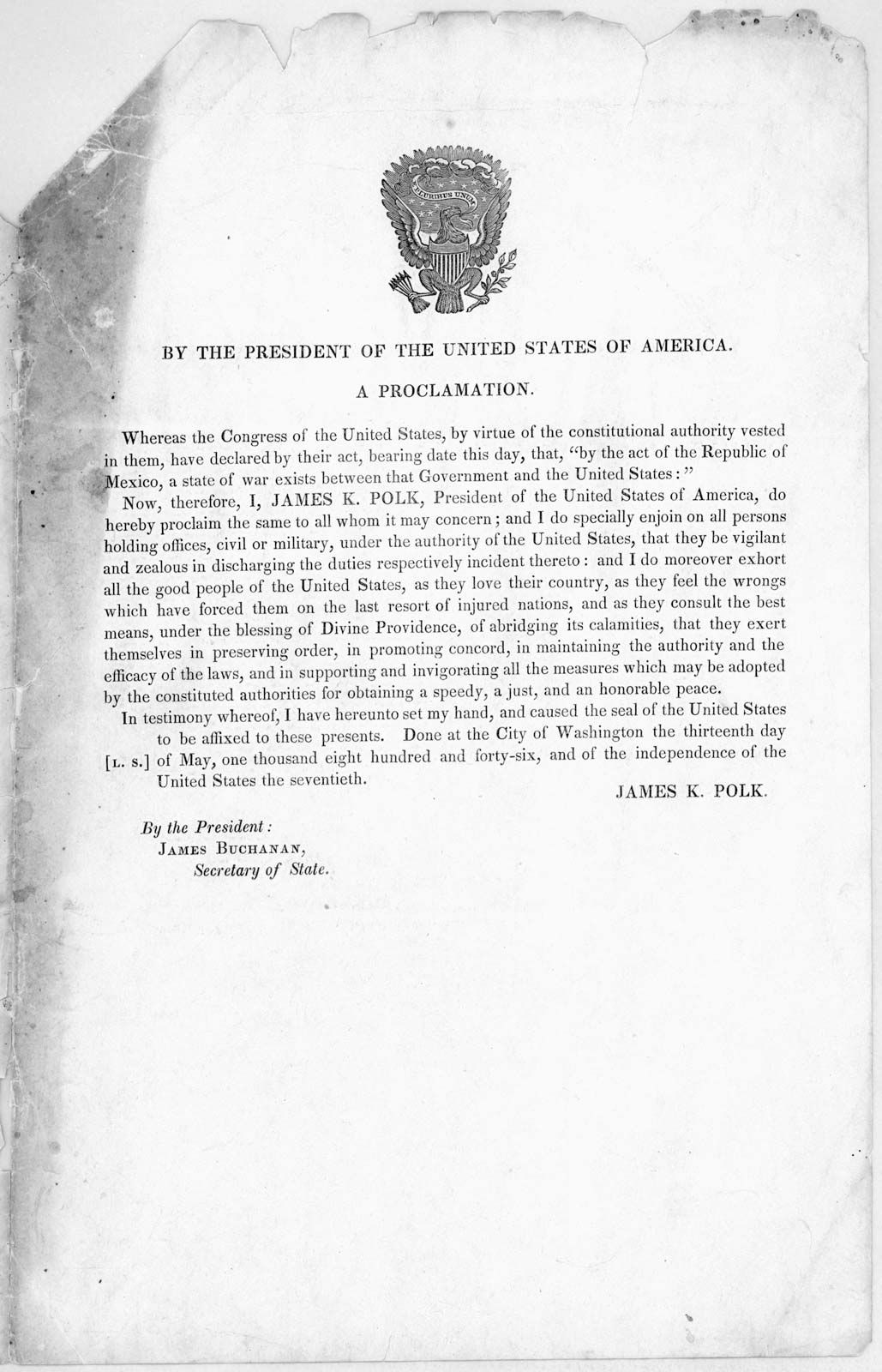

Mexican-American War: U.S. declaration of war

Mexican-American War: U.S. declaration of war

Alt Text: 1846 leaflet of President James K. Polk’s proclamation declaring war against Mexico.

Congress, swayed by Polk’s message and public sentiment, formally declared war on Mexico on May 13, 1846. However, the declaration was not without opposition. Notably, the Whig party and abolitionist groups voiced strong dissent, questioning the legitimacy of the war and accusing Polk of deliberately provoking conflict to seize Mexican territories.

Domestic Opposition and Moral Debates: The Spot Resolutions and Civil Disobedience

Despite the initial surge of patriotic fervor, the Mexican-American War faced significant opposition within the United States. Many, particularly Whigs and abolitionists, viewed the war as unjust, immoral, and driven by expansionist greed and the desire to expand slavery. This domestic opposition manifested in various forms, from political challenges to acts of civil disobedience.

One of the most prominent challenges to Polk’s war justification came from Abraham Lincoln, then a young Whig Congressman from Illinois. Lincoln introduced the “Spot Resolutions,” demanding that President Polk specify the exact “spot” where American blood was shed and prove that it was indeed on American soil. These resolutions directly challenged the factual basis of Polk’s war message and highlighted the contested nature of the territory where the initial clash occurred.

Alt Text: Earliest known photograph of Abraham Lincoln, taken circa 1846-1847 during his term as Congressman.

While Lincoln’s resolutions did not gain widespread support in Congress, they symbolized the growing moral and political opposition to the war. Figures like Henry David Thoreau also voiced their dissent through acts of civil disobedience. Thoreau famously refused to pay taxes in protest of the war, arguing that it was an immoral act of aggression. His essay “Civil Disobedience,” written in response to his brief imprisonment for tax evasion, became a foundational text for movements advocating nonviolent resistance to unjust laws and wars.

Abolitionists further condemned the war as a pro-slavery conspiracy, fearing that newly acquired territories would become slave states, thus increasing the political power of the South and perpetuating the institution of slavery. This perspective added another layer of complexity to the domestic debate, linking the war to the already simmering tensions over slavery that would eventually erupt into the American Civil War.

Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo and Lasting Consequences

Despite domestic opposition, the Mexican-American War resulted in a decisive victory for the United States. American forces, though often outnumbered, consistently outmaneuvered and defeated the Mexican army in a series of key battles, from Palo Alto and Buena Vista to Cerro Gordo and Chapultepec. By 1847, U.S. forces had occupied Mexico City, forcing the Mexican government to negotiate peace.

The war officially ended with the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, signed in February 1848. Under the terms of the treaty, Mexico ceded to the United States a vast expanse of territory encompassing present-day California, Nevada, Utah, Arizona, New Mexico, and parts of Colorado, Wyoming, Kansas, and Oklahoma. This territory, known as the Mexican Cession, increased the size of the United States by approximately one-third. In exchange, the U.S. paid Mexico $15 million and assumed claims of American citizens against Mexico.

The Mexican-American War had profound and lasting consequences for both nations. For the United States, it fulfilled the expansionist dreams of Manifest Destiny, solidified its position as a continental power, and provided access to valuable resources and strategic locations. However, the territorial gains also reignited the debate over slavery, exacerbating sectional tensions that ultimately led to the Civil War.

For Mexico, the war was a national trauma, resulting in the loss of a significant portion of its territory and a deep sense of humiliation. The war further destabilized the already fragile Mexican political landscape and left a legacy of resentment and mistrust towards the United States that continues to resonate in contemporary US-Mexico relations. The Mexican-American War remains a crucial historical event to understand the complex and often fraught history between these two neighboring countries.

Conclusion: A War of Expansion and Enduring Scars

The Mexican-American War was a transformative event driven by American expansionism, territorial disputes, and the ideology of Manifest Destiny. While it resulted in significant territorial gains for the United States and solidified its continental ambitions, it came at a high cost, both in terms of human lives and the exacerbation of domestic divisions over slavery. For Mexico, the war was a devastating loss, marking a painful chapter in its national history and leaving a lasting scar on its relationship with the United States. The legacies of the Mexican-American War continue to shape the political, social, and cultural landscapes of both nations, reminding us of the complex and enduring consequences of territorial expansion and international conflict.