Nestled in the stunning landscapes of New Mexico, Bandelier National Monument offers a captivating journey into the past. Our recent exploration of this remarkable site, revisiting it after two decades, reignited our awe for the ancient cliff dwellings and pueblo ruins that define this area. Bandelier, a jewel of New Mexico, is more than just a scenic destination; it’s a profound connection to the Ancestral Pueblo people who called this canyon home for centuries.

Image: Entering a cavate dwelling in Bandelier National Monument, showcasing the ladder access.

Image: Entering a cavate dwelling in Bandelier National Monument, showcasing the ladder access.

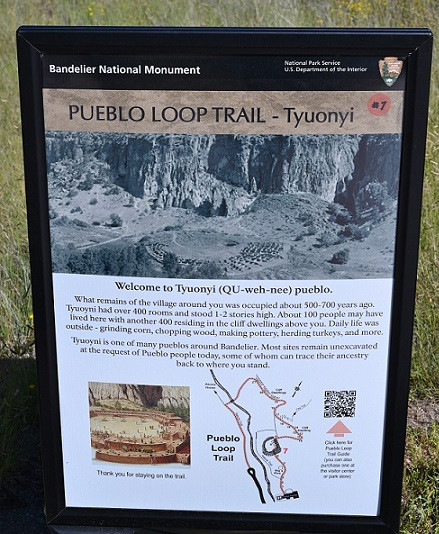

Exploring the Pueblo Loop Trail in Bandelier National Monument

The Pueblo Loop Trail, a gently winding path through Frijoles Canyon, is the heart of the Bandelier experience. As you traverse this trail, the towering cliffs of volcanic tuff, sculpted by time and the elements, rise dramatically beside you. During our early September visit, the late summer and early fall wildflowers added vibrant splashes of color to the already breathtaking scenery, enhancing the natural beauty of New Mexico.

Image: Wildflowers and shadows along the Pueblo Loop Trail in Bandelier, New Mexico.

Image: Wildflowers and shadows along the Pueblo Loop Trail in Bandelier, New Mexico.

Today, Frijoles Canyon exudes tranquility, but imagine this serene landscape buzzing with life around 800 years ago. This canyon was once a thriving hub for hundreds of indigenous people, the Ancestral Puebloans. They were skilled farmers, hunters, and foragers, expertly utilizing the resources of the land. Their ingenuity is evident in the homes and storage spaces they carved into the soft cliffs, known as cavates, and the multi-story pueblos they constructed on the canyon floor.

Image: Sign for Pueblo Loop Trail at Bandelier National Monument, indicating the historical significance of the area.

Image: Sign for Pueblo Loop Trail at Bandelier National Monument, indicating the historical significance of the area.

According to the National Park Service website, the Ancestral Pueblo people inhabited this area from approximately 1150 CE to 1550 CE. Their diet was centered around corn, beans, and squash, supplemented by native plants and game such as deer, rabbit, and squirrel. Domesticated turkeys were valuable for both their feathers and meat, while dogs played a role in hunting and companionship. By 1550, a combination of factors, including land depletion and severe drought, led the Ancestral Pueblo people to relocate to pueblos along the Rio Grande.

Bandelier National Monument, named after Adolph Bandelier, a 19th-century anthropologist whose research highlighted the site’s importance, invites visitors to step back in time. Exploring the canyon and venturing into the accessible cavates offers a tangible connection to this rich history. This New Mexico treasure is a testament to the enduring legacy of its early inhabitants.

Kivas: Ceremonial Centers of Ancestral Pueblo Life

As you walk the Pueblo Loop Trail and approach the cliff dwellings, you’ll encounter Big Kiva, a significant archaeological feature. Kivas are circular, subterranean structures that served as spaces for religious ceremonies and community gatherings. These sacred spaces were accessed via a ladder through a roof made of posts and mud. While Big Kiva’s roof is no longer intact, the stone circle that defines its perimeter remains a powerful reminder of its past importance.

Image: Big Kiva along the Pueblo Loop Trail in Bandelier, showcasing the circular stone structure.

Image: Big Kiva along the Pueblo Loop Trail in Bandelier, showcasing the circular stone structure.

Further along the trail, a smaller, excavated kiva provides a more intimate glimpse into these ceremonial spaces. These kivas are central to understanding the spiritual and social life of the Ancestral Pueblo people at Bandelier.

Image: A smaller, excavated kiva at Bandelier, illustrating the subterranean structure.

Image: A smaller, excavated kiva at Bandelier, illustrating the subterranean structure.

Scattered near the kivas are the ruins of stone block homes, foundations of dwellings that once stood as part of the bustling canyon floor village. These remnants offer a sense of the community that thrived in this New Mexico canyon.

Image: Pueblo ruins and yellow wildflowers in Bandelier National Monument, highlighting the blend of nature and history.

Image: Pueblo ruins and yellow wildflowers in Bandelier National Monument, highlighting the blend of nature and history.

Informational signs within Bandelier National Monument reveal that approximately 100 people may have resided in the canyon floor houses, while an estimated 400 lived in the cavates carved into the cliff face. During the summer months, they would ascend to the mesa top to cultivate their crops, a testament to their resilience and connection to the land. Imagine the daily climb to tend to their fields high above the canyon floor!

Cavates: Homes Carved into the Cliffs

The cavates of Bandelier are perhaps the most iconic feature of the monument. Visitors are permitted to enter cavates that are equipped with ladders, offering a unique opportunity to experience these ancient dwellings firsthand. A park ranger explained that the Ancestral Puebloans constructed ladders from single poles with notched footholds or by attaching wooden rungs to two poles. Contemplate the agility required to navigate these ladders daily, potentially carrying children or supplies, in all kinds of weather.

Image: Ladder leading to a cavate dwelling in Bandelier’s cliffs, showing the access to these unique homes.

Image: Ladder leading to a cavate dwelling in Bandelier’s cliffs, showing the access to these unique homes.

Yet, they thrived in these cliffside homes. Bandelier’s website (https://www.nps.gov/band/learn/historyculture/carved.htm) notes that over a thousand of these rooms are found within Frijoles Canyon’s walls. These cavate villages were inhabited by generations of Ancestral Pueblo people. Marks on the ceilings reveal that tools like digging sticks and sharpened stones were used to enlarge natural openings in the volcanic tuff. While most cavates are single rooms, some are interconnected. Many originally had masonry structures, up to three stories high, built in front, crafted from tuff blocks and mud mortar.

Image: Interior view of a cavate in Bandelier, showing the carved space and textures.

Image: Interior view of a cavate in Bandelier, showing the carved space and textures.

These front rooms served various purposes, including weaving, grinding corn, and storage. Many cavates feature carved and plastered niches, likely used for storing pottery and household items. Sockets in the ceilings and anchors in the floors indicate the presence of looms for weaving. The cavates themselves also served as living quarters, offering shelter and a unique way of life within the cliffs of New Mexico.

Image: A cavate doorway with a ladder, framing a view from within the cliff dwelling.

Image: A cavate doorway with a ladder, framing a view from within the cliff dwelling.

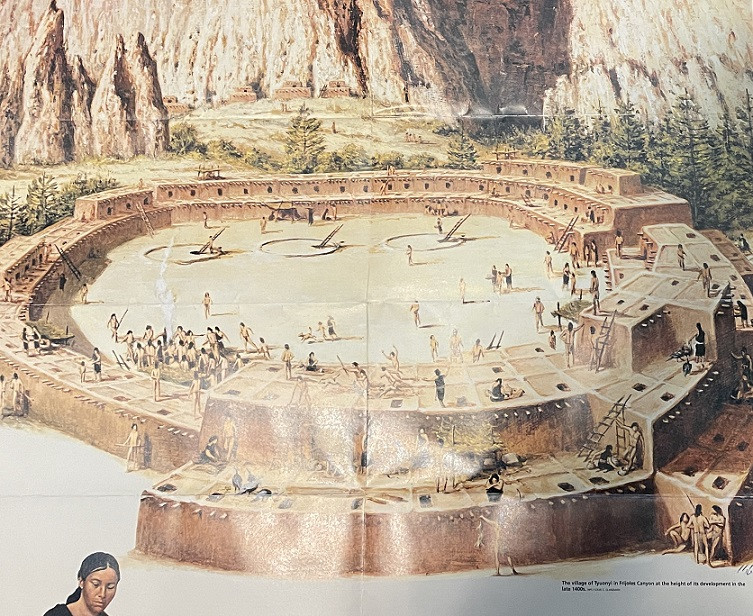

Tyuonyi Pueblo: Village Center Below the Cliffs

From the vantage point of the cavates, one can look down upon the ruins of Tyuonyi Pueblo. This village, built in a circular layout, was situated on the canyon floor. The remaining foundations outline what was once a lively village comprised of multi-story rooms, a bustling center of community life around 800 years ago.

Image: View from a cavate overlooking the Tyuonyi Pueblo ruins below in Bandelier.

Image: View from a cavate overlooking the Tyuonyi Pueblo ruins below in Bandelier.

The circular foundation reveals the layout of Tyuonyi Pueblo, giving visitors a sense of the scale and organization of this ancient village. Walking among these ruins is a powerful experience, connecting you to the daily lives of the people who once thrived here in New Mexico.

Image: Close-up of the Tyuonyi Pueblo ruins, showing the stone foundations and surrounding rocks.

Image: Close-up of the Tyuonyi Pueblo ruins, showing the stone foundations and surrounding rocks.

An image from the National Park Service brochure vividly reconstructs Tyuonyi Pueblo, showcasing the multi-story structures and kivas with ladders emerging from the center. This image helps visualize the complete village, with masonry structures in front of some cavates along the cliff wall in the background.

Image: Image from a Bandelier National Monument brochure depicting a reconstruction of Tyuonyi Pueblo and cliff dwellings.

Image: Image from a Bandelier National Monument brochure depicting a reconstruction of Tyuonyi Pueblo and cliff dwellings.

Talus House and the Ingenuity of Puebloan Construction

Along the base of the cliff, Talus House stands as a reconstruction from the early 1900s, demonstrating the masonry structures that would have fronted some cavates. It’s important to note that the window seen in the reconstruction is not historically accurate; it was added to allow visitors to see inside. Originally, access would have been through a ladder via the roof.

Image: Talus House reconstruction in Bandelier, illustrating the masonry front of a cavate dwelling.

Image: Talus House reconstruction in Bandelier, illustrating the masonry front of a cavate dwelling.

The Ancestral Pueblo people were clearly skilled climbers and builders, adept at navigating and constructing homes in this challenging cliffside environment. Talus House highlights their architectural ingenuity and adaptation to the landscape of New Mexico.

Image: Another view of Talus House, emphasizing the reconstructed masonry structure.

Image: Another view of Talus House, emphasizing the reconstructed masonry structure.

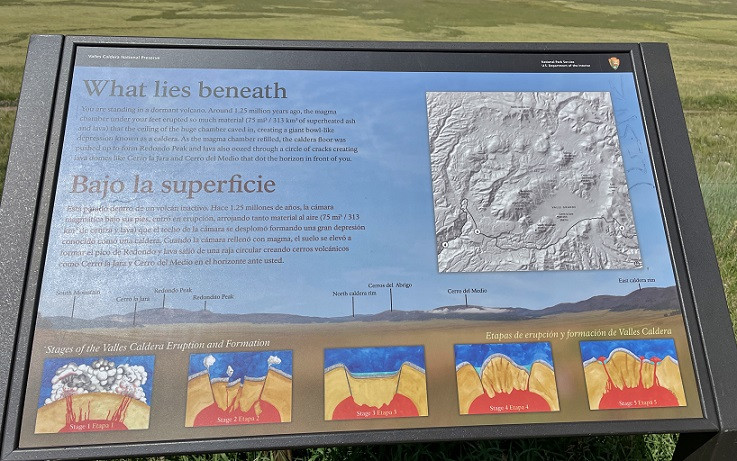

The volcanic rock of Frijoles Canyon, characterized by its porous and holey texture, originated from ash flows from Valles Caldera, which we explored later the same day. This geological connection underscores the dramatic natural forces that shaped the landscape and provided the very material for the cliff dwellings at Bandelier.

Image: Close-up of the holey volcanic rock in Frijoles Canyon, the tuff from Valles Caldera.

Image: Close-up of the holey volcanic rock in Frijoles Canyon, the tuff from Valles Caldera.

Eroded stone pillars within the canyon evoke human-like forms, adding a touch of whimsy to the geological formations. One pillar appears seated, another standing, gazing out over the canyon, silent sentinels of time.

Image: Eroded rock pillars in Bandelier, resembling figures looking out over the canyon.

Image: Eroded rock pillars in Bandelier, resembling figures looking out over the canyon.

In another section of the cliff, skull-like cave formations add an intriguing, almost surreal element to the natural artistry of the canyon walls.

Image: Skull-like cave formations in the cliffs of Bandelier, showcasing the unique rock shapes.

Image: Skull-like cave formations in the cliffs of Bandelier, showcasing the unique rock shapes.

Looking back towards Talus House, the view encapsulates the blend of human history and natural beauty that defines Bandelier National Monument.

Image: View back towards Talus House from the Pueblo Loop Trail, with canyon scenery.

Image: View back towards Talus House from the Pueblo Loop Trail, with canyon scenery.

Cholla cacti and wildflowers thrive in this New Mexico environment, adding pops of color to the rugged landscape and demonstrating the resilience of life in this arid region.

Image: Cholla cactus and wildflowers in Bandelier with mountain views in the distance.

Image: Cholla cactus and wildflowers in Bandelier with mountain views in the distance.

Even more wildflowers bloom along the trail, further enhancing the visual appeal of the hike and highlighting the diverse flora of New Mexico.

Image: White wildflowers blooming in Bandelier National Monument, adding to the natural beauty.

Image: White wildflowers blooming in Bandelier National Monument, adding to the natural beauty.

Long House: Evidence of Multi-Story Cliff Dwellings and Petroglyphs

One section of the cliff face, known as Long House, reveals clear evidence of multi-story homes built directly against the cliff wall. This area showcases the sophisticated construction techniques of the Ancestral Pueblo people.

Image: Remains of Long House cliff dwellings in Bandelier, showing the multi-story construction.

Image: Remains of Long House cliff dwellings in Bandelier, showing the multi-story construction.

Rows of holes in the soft rock mark where wooden poles, called vigas, once provided support for the roofs of these cliff dwellings. These structural details offer insights into the building methods used centuries ago.

Image: Close-up of cliff dwelling remains at Long House, showing viga holes in the rock.

Image: Close-up of cliff dwelling remains at Long House, showing viga holes in the rock.

Hundreds of petroglyphs, carvings into the stone, endure to this day, depicting figures such as turkeys and dogs. These ancient artworks provide valuable clues about the lives, beliefs, and environment of the people who lived at Bandelier.

Image: Cliff dwelling remains with petroglyphs carved into the stone at Bandelier.

Image: Cliff dwelling remains with petroglyphs carved into the stone at Bandelier.

A painted pictograph, a rarer form of rock art, has also survived and is now protected under glass, preserving this delicate piece of history for future generations.

Image: A protected pictograph (painted rock art) at Bandelier National Monument.

Image: A protected pictograph (painted rock art) at Bandelier National Monument.

Datura and red morning glory, growing wild, add vibrant colors to the natural flora around the cliff dwellings, showcasing the biodiversity of the New Mexico landscape.

Image: Datura and red morning glory wildflowers growing near the cliff dwellings in Bandelier.

Image: Datura and red morning glory wildflowers growing near the cliff dwellings in Bandelier.

More cholla cacti with wildflowers continue to enhance the scenic beauty of the trail, demonstrating the harmonious blend of desert flora and historical significance at Bandelier.

Image: Cholla cactus with yellow wildflowers in Bandelier, emphasizing the desert flora.

Image: Cholla cactus with yellow wildflowers in Bandelier, emphasizing the desert flora.

A sphinx moth, with colors mirroring the pictograph, captivated our attention, flitting among the flowers and feeding on nectar with its long proboscis. This moment of natural beauty underscored the vibrant ecosystem of Bandelier.

Image: Sphinx moth feeding on wildflowers at Bandelier, showcasing the local wildlife.

Image: Sphinx moth feeding on wildflowers at Bandelier, showcasing the local wildlife.

A zoom captures the sphinx moth in flight, a dynamic moment illustrating the active wildlife within the monument.

Image: Zoomed-in shot of a sphinx moth in flight near flowers at Bandelier.

Image: Zoomed-in shot of a sphinx moth in flight near flowers at Bandelier.

The sphinx moth dining on the wing, a fascinating example of nature’s intricate details, further enriched our experience at Bandelier.

Image: Sphinx moth feeding while hovering near flowers in Bandelier National Monument.

Image: Sphinx moth feeding while hovering near flowers in Bandelier National Monument.

The panoramic canyon view encapsulates the grandeur of the landscape, a vista that has remained largely unchanged for centuries, connecting modern visitors to the ancient past.

Image: Expansive canyon view from the Pueblo Loop Trail in Bandelier National Monument.

Image: Expansive canyon view from the Pueblo Loop Trail in Bandelier National Monument.

More cholla cacti and yellow wildflowers dot the landscape, reinforcing the unique beauty of the New Mexico environment within Bandelier.

Image: Cholla cactus with vibrant yellow flowers, common in the Bandelier landscape.

Image: Cholla cactus with vibrant yellow flowers, common in the Bandelier landscape.

Continuing along the trail towards Alcove House, we witnessed a dramatic scene of nature in action: a larger snake consuming a smaller snake. Though the photo is slightly blurry due to distance, it captures a rare and compelling moment of wildlife behavior.

Image: A snake eating another snake along the trail to Alcove House in Bandelier, a wildlife sighting.

Image: A snake eating another snake along the trail to Alcove House in Bandelier, a wildlife sighting.

Alcove House: Reaching New Heights

On previous visits to Bandelier, we had not ventured as far as Alcove House. This time, David was eager to ascend to this large cave, situated 140 feet up the cliff face. Access is via a series of four wooden ladders and stone steps, an adventurous climb. I opted to stay below, capturing photos of his ascent.

Image: Ladders leading up to Alcove House cave in Bandelier, showing the vertical climb.

Image: Ladders leading up to Alcove House cave in Bandelier, showing the vertical climb.

David begins his climb up the ladders to Alcove House, illustrating the scale and height of the ascent.

Image: Person climbing the ladders towards Alcove House cave at Bandelier.

Image: Person climbing the ladders towards Alcove House cave at Bandelier.

He captured this photo looking up the third ladder, emphasizing the vertical nature of the climb and the perspective from below.

Image: View looking up the ladders to Alcove House cave, taken from the third ladder.

Image: View looking up the ladders to Alcove House cave, taken from the third ladder.

From inside Alcove House, the view is breathtaking. A reconstructed kiva is located within this large cave, and it’s estimated that as many as 25 people may have lived in this elevated dwelling at one time.

Image: Interior of Alcove House cave in Bandelier, with a reconstructed kiva and panoramic view.

Image: Interior of Alcove House cave in Bandelier, with a reconstructed kiva and panoramic view.

The descent from Alcove House, while offering different views, is a necessary part of the journey, completing the round trip to this remarkable location.

Image: Ladders descending from Alcove House cave in Bandelier, completing the climb.

Image: Ladders descending from Alcove House cave in Bandelier, completing the climb.

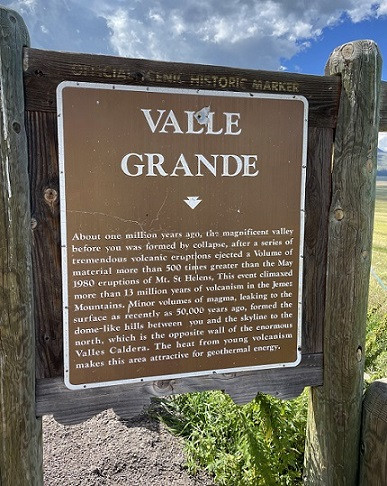

Valles Caldera National Preserve: Source of the Volcanic Landscape

Bandelier National Monument is undeniably captivating, and our return visit reaffirmed its allure. After a picnic lunch, we drove just 30 minutes west to Valles Caldera National Preserve. This stunning valley is the geological origin of the volcanic rock that forms the cliffs of Bandelier. Where once volcanic destruction reigned, a beautiful green valley now unfolds.

Image: Expansive view of Valles Caldera National Preserve, a vast green valley.

Image: Expansive view of Valles Caldera National Preserve, a vast green valley.

A bullet-holed sign provides a stark reminder of the area’s history: about one million years ago, this valley was created by a massive volcanic collapse, following eruptions 500 times greater than the 1980 Mount St. Helens eruption. More recent, smaller magma flows, as recent as 50,000 years ago, formed the dome-like hills visible to the north.

Image: Sign at Valles Caldera detailing its volcanic formation history.

Image: Sign at Valles Caldera detailing its volcanic formation history.

“You are standing in a dormant volcano,” another sign explains. Having visited other volcanic landscapes in our travels, this sign added another layer of geological context to our New Mexico journey.

Image: Sign stating “You are standing in a dormant volcano” at Valles Caldera.

Image: Sign stating “You are standing in a dormant volcano” at Valles Caldera.

The valley grasses glowed a mossy green, surrounded by moody, blue-green hills, creating a breathtaking panorama. The beauty of Valles Caldera offers a powerful contrast to the dramatic volcanic forces that shaped it.

Image: Lush green valley of Valles Caldera with surrounding hills and mountains.

Image: Lush green valley of Valles Caldera with surrounding hills and mountains.

Prairie dogs make their homes in Valles Caldera, and these charming rodents were active, darting across the road as we paused to observe them, adding a touch of wildlife to the scenic preserve.

Image: Prairie dogs in Valles Caldera National Preserve, showing the local wildlife.

Image: Prairie dogs in Valles Caldera National Preserve, showing the local wildlife.

A close-up of a prairie dog captures the cute and curious nature of these valley inhabitants.

Image: Close-up portrait of a prairie dog in Valles Caldera.

Image: Close-up portrait of a prairie dog in Valles Caldera.

Anderson Scenic Overlook near Los Alamos: Final Vista

From Valles Caldera, we drove towards Los Alamos. Upon entering Los Alamos, we encountered security checkpoints where every car was stopped and questioned. We were advised against photographing buildings on the right side of the road, a reminder of the town’s significant, albeit somber, history as the birthplace of the atomic bomb. We drove through without taking photos, satisfying our curiosity about this historically important location.

Leaving Los Alamos, heading back to Santa Fe, we were rewarded with a stunning view of orange mesas framed by olive green trees, with blue mountains in the distance. We stopped at the Anderson Scenic Overlook to soak in one last breathtaking vista of “The Land of Enchantment,” New Mexico, on our final day of our trip.

Image: Mesa landscape view from Anderson Scenic Overlook near Los Alamos, New Mexico.

Image: Mesa landscape view from Anderson Scenic Overlook near Los Alamos, New Mexico.

This visit to Bandelier National Monument and Valles Caldera, capped off by the views from Anderson Scenic Overlook, concluded our New Mexico road trip. It was a journey through history, geology, and natural beauty, leaving us with lasting memories of this enchanting state. If you are planning a trip to New Mexico, Bandelier National Monument is an essential destination, offering a unique and profound experience of the ancient Southwest.