The 19th century was a period of intense upheaval for Mexico, marked by internal strife and foreign interference. At the heart of this tumultuous era was the Mexican Civil War, a conflict that not only shaped the nation’s destiny but also drew in international players, most notably France. The French intervention in Mexico, orchestrated by Emperor Napoleon III, became inextricably linked to the American Civil War, creating a complex geopolitical landscape with lasting consequences for all involved.

In 1857, Mexico plunged into a civil war, a battle for the nation’s soul between two opposing factions: the Liberals, advocating for reform and led by Benito Juárez, and the Conservatives, who sought to maintain the old order under Félix Zuloaga. The Conservatives, holding sway from Mexico City, clashed fiercely with the Liberals based in Veracruz. By 1859, the United States recognized the legitimacy of the Juárez government, a significant diplomatic victory for the Liberals. In January 1861, Liberal forces captured Mexico City, strengthening Juárez’s position. However, the protracted instability had severely impacted Mexico’s economy, leading to a mounting foreign debt that the government struggled to repay.

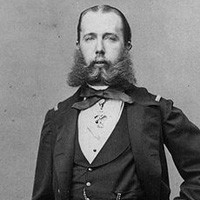

Maximilian of Habsburg, Emperor of Mexico during the French Intervention, a consequence of the Mexican Civil War

Maximilian of Habsburg, Emperor of Mexico during the French Intervention, a consequence of the Mexican Civil War

Amidst this internal conflict, the United States, under Secretary of State William Henry Seward, proposed a plan to alleviate Mexico’s financial woes. Seward offered loans in exchange for mining concessions, with the ominous condition that failure to repay would result in the cession of Baja California and other Mexican territories. While U.S. diplomat Thomas Corwin negotiated a treaty with Mexican representative Manuel Maria Zamacona, the U.S. Congress ultimately rejected it, wary of diverting funds from the looming American Civil War.

European Powers Exploit Mexican Instability

Facing limited options, Juárez made the difficult decision to suspend payments on Mexico’s foreign debt for two years. This action provided the pretext for European intervention. Spain, France, and Britain, seeking to recover their debts, convened in London and signed a tripartite agreement in October 1861. European forces landed in Veracruz in December of the same year. While Juárez called for national resistance, Mexican Conservatives saw the European forces as potential allies against the Liberals.

However, the ambitions of the European powers were not uniform. While Britain and Spain had limited objectives focused on debt collection, Napoleon III of France harbored grander designs. He envisioned establishing a French client state in Mexico as part of a broader strategy to expand French influence. As French intentions became clear, Spanish and British forces withdrew, leaving France to pursue its imperialistic goals. French forces advanced, capturing Mexico City. In 1863, Napoleon III offered the throne of Mexico to Maximilian of Habsburg, an Austrian Archduke. Maximilian accepted and arrived in Mexico in 1864, becoming Emperor of Mexico, propped up by French bayonets. Despite Maximilian’s Conservative government controlling a significant portion of the country, Juárez and the Liberals maintained their resistance, particularly in northwestern Mexico and along the Pacific coast.

Benito Juárez, Liberal President of Mexico during the Mexican Civil War and French Intervention, resisting European influence

Benito Juárez, Liberal President of Mexico during the Mexican Civil War and French Intervention, resisting European influence

The United States, itself embroiled in its own Civil War, could only voice disapproval of the French intervention. Secretary Seward issued statements of protest, but direct intervention was impossible. Furthermore, both Seward and President Abraham Lincoln were cautious not to provoke Napoleon III, fearing French support for the Confederacy. The U.S. government also declined requests from other Latin American nations for a united American response. However, Matías Romero, the Mexican Minister to the United States, skillfully cultivated American sympathy for Mexico’s plight, gradually shifting U.S. policy towards stronger support for Juárez.

The Tide Turns: French Withdrawal and the End of Maximilian’s Empire

The conclusion of the American Civil War in 1865 dramatically altered the landscape. Juárez’s forces began to gain momentum against Maximilian’s regime. Maximilian, who had arrived in Mexico with limited understanding of the complex political dynamics, alienated his Conservative base by attempting to implement liberal policies. Simultaneously, he failed to gain the support of the Liberals, who viewed him as a foreign imposition and a tool of the Conservatives and French.

By 1865, Liberal military successes significantly weakened Maximilian’s position. U.S. Generals Ulysses S. Grant and Philip Henry Sheridan, acting independently of Seward’s initially cautious approach, began to provide covert support to Juárez along the Texas-Mexico border. Simultaneously, the French intervention became increasingly unpopular at home and a drain on the French treasury. In January 1866, Napoleon III ordered the withdrawal of French troops, scheduled in stages from November 1866 to November 1867. Seward, now emboldened, warned Austria against replacing French troops with Austrian forces. The threat of U.S. intervention deterred Austria from sending reinforcements.

Abandoned by European support, Maximilian’s empire crumbled. He was captured by Juárez’s forces, court-martialed, and executed, marking the definitive end of European intervention in Mexico. Seward hoped that U.S. support for Juárez would foster stronger relations with Mexico, ultimately envisioning Mexico’s eventual integration into the United States as part of his expansionist strategy.

Throughout the French intervention, the official U.S. policy aimed to avoid direct confrontation with France while expressing disapproval of French actions in Mexico. Neutrality was maintained until 1866 when the U.S. began providing more overt support to Juárez, coinciding with France’s decision to withdraw. While U.S. support during this period temporarily improved U.S.-Mexican relations, subsequent border disputes under Secretary of State William Evarts would later strain the goodwill established during Seward’s tenure, demonstrating the complex and often fraught relationship between the two nations in the aftermath of the Mexican Civil War and French intervention.