The Gulf Of Mexico Oil Spill, also known as the Deepwater Horizon oil spill, stands as the largest marine oil spill in history. This environmental catastrophe began on April 20, 2010, with a devastating explosion on the Deepwater Horizon oil rig, located approximately 41 miles off the coast of Louisiana. The subsequent sinking of the rig two days later unleashed an uncontrolled flow of crude oil into the Gulf, causing widespread environmental and economic damage.

The Deepwater Horizon Explosion and Initial Leak

The Deepwater Horizon rig was operating in the Macondo oil prospect within the Mississippi Canyon, drilling an oil well nearly 5,000 feet below the surface of the Gulf of Mexico, extending thousands of feet further into the seabed. Owned by Transocean and leased by BP, the rig was in the process of sealing the well with a concrete core for future use when disaster struck. On the evening of April 20, a surge of highly pressurized natural gas breached this recently installed concrete barrier. Investigations later revealed that the concrete core, possibly weakened by a nitrogen-infused mixture intended to accelerate curing, was unable to withstand the immense pressure from below. A similar incident involving faulty concrete cores had occurred on a BP rig in the Caspian Sea in 2008, raising questions about safety protocols and risk assessment.

Fireboats battling the Deepwater Horizon oil rig fire in the Gulf of Mexico after the explosion.

Fireboats battling the Deepwater Horizon oil rig fire in the Gulf of Mexico after the explosion.

The escaping natural gas shot up the rig’s riser pipe to the platform, where it ignited in a massive explosion. The immediate impact was tragic: eleven workers were killed, and seventeen others were injured. Two days later, on April 22, the Deepwater Horizon capsized and sank. This sinking ruptured the riser, a crucial conduit for drilling mud which normally counteracted the upward pressure of oil and gas. With this counter-pressure gone, oil began to gush unchecked into the Gulf of Mexico. Initial estimates from BP understated the severity, suggesting a leak of around 1,000 barrels per day. However, U.S. government officials later estimated the flow peaked at a staggering 60,000 barrels per day, highlighting the immense scale of the unfolding environmental disaster.

Attempts to Stop the Leak

The immediate aftermath of the Deepwater Horizon sinking focused on containing the massive oil leak. A primary fail-safe mechanism, the blowout preventer (BOP), designed to seal off the well in emergencies, malfunctioned. Forensic analysis revealed that the BOP’s blind shear rams, powerful blades intended to cut through the oil pipe, failed because the pipe buckled under the pressure of the surging gas and oil. Some reports even suggested the rams activated prematurely, potentially exacerbating the pipe rupture.

Debris and crude oil slicks on the Gulf of Mexico surface after the Deepwater Horizon rig sank.

Debris and crude oil slicks on the Gulf of Mexico surface after the Deepwater Horizon rig sank.

Early attempts to place a large containment dome over the primary leak site failed due to the formation of gas hydrates – ice-like structures of gas and water – which became buoyant and disrupted the containment effort. A “top kill” attempt, involving pumping heavy drilling mud into the well to block the oil flow, also proved unsuccessful.

In early June, BP deployed a Lower Marine Riser Package (LMRP) cap. After detaching the damaged riser from the BOP, this cap was lowered and loosely fitted over the BOP. While not a perfect seal, it allowed for the siphoning of approximately 15,000 barrels of oil per day to a tanker. An additional collection system, utilizing multiple devices connected to the BOP, increased the daily collection rate to about 25,000 barrels.

In July, the LMRP cap was temporarily removed to install a more permanent capping stack, which was in place by July 12. Despite the improved seal, by this point, it was estimated that approximately 4.9 million barrels of oil had already leaked into the Gulf of Mexico, with only about 800,000 barrels captured. On August 3, a “static kill” procedure, similar to the top kill but made safer by the capping stack, was successfully executed by pumping drilling mud through the BOP at lower pressures. The defective BOP and capping stack were then removed and replaced with a functional BOP in early September.

The final step to permanently seal the well was the “bottom kill.” This involved drilling two relief wells that intersected the original wellbore. On September 17, the bottom kill was successfully completed through the first relief well by pumping cement through it. The second relief well, intended as a backup, was not needed. On September 19, after rigorous pressure tests, it was officially declared that the well was completely sealed, marking the end of the uncontrolled oil flow after 87 days.

Environmental and Ecological Impact

Even as efforts focused on stopping the leak, concerns grew about the environmental consequences of the massive oil spill. Initial claims of subsurface plumes of dispersed hydrocarbons were initially downplayed, but later verified. These microscopic oil droplets presented an unknown threat to the marine ecosystem. Furthermore, a thick layer of oil was discovered on the seafloor in September, challenging earlier optimistic predictions about the rapid dissipation of the oil.

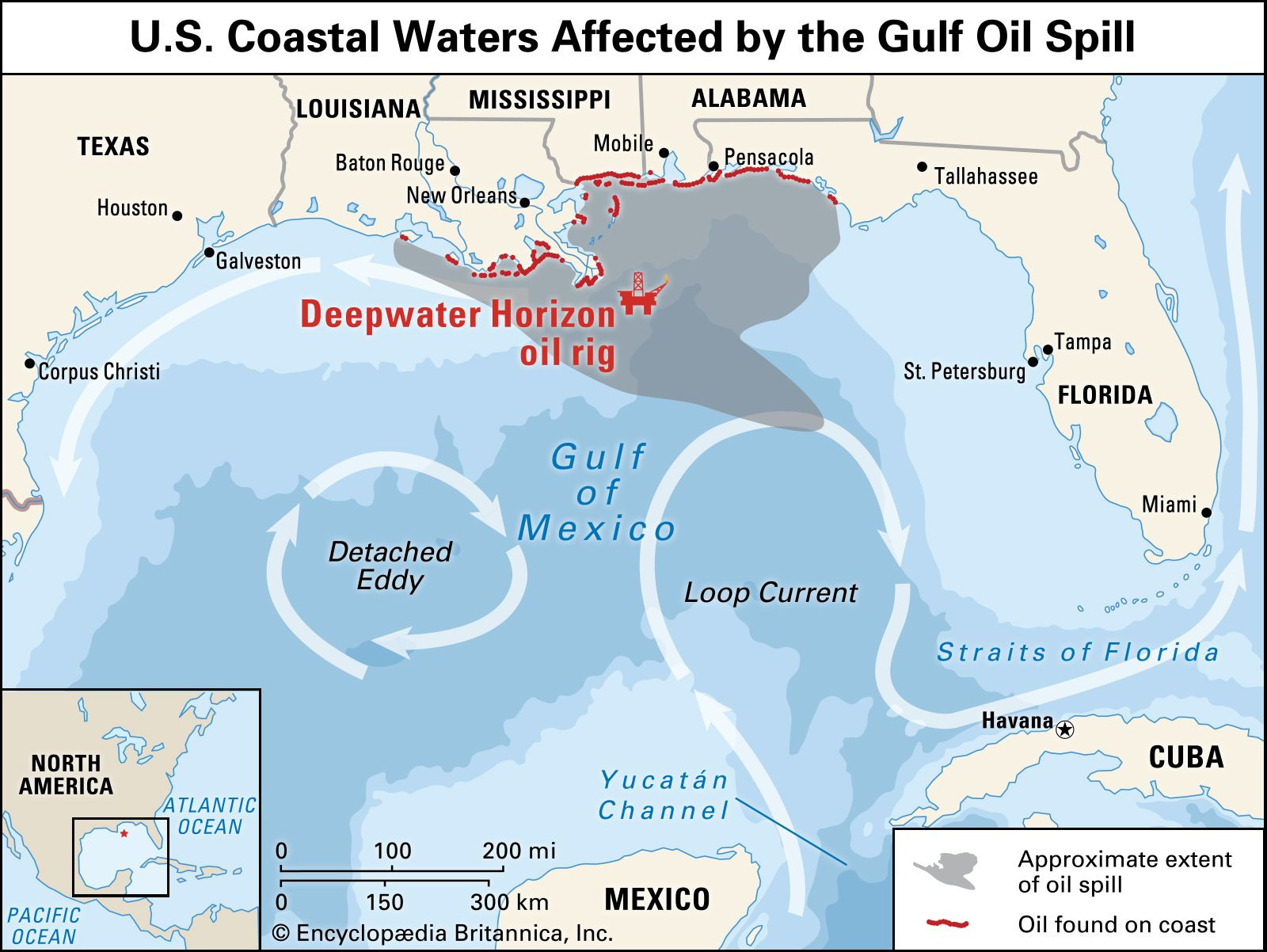

Map showing the spread of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico, impacting the Gulf Coast.

Map showing the spread of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico, impacting the Gulf Coast.

The Gulf of Mexico oil spill had a devastating impact on marine life. Birds were particularly vulnerable, with estimates suggesting up to 800,000 fatalities due to oil ingestion and the disruption of their body temperature regulation. Brown pelicans and laughing gulls were among the most affected species. Marine mammals, sea turtles, and fish populations also suffered significant harm. The long-term ecological consequences of the Deepwater Horizon disaster are still being studied, but the spill undoubtedly caused lasting damage to the Gulf of Mexico ecosystem and highlighted the risks associated with deepwater oil drilling.

While naturally occurring bacteria adapted to consuming seabed oil seeps were thought to have played a role in breaking down some of the spilled oil, the sheer volume of the Deepwater Horizon spill overwhelmed natural processes. The disaster served as a stark reminder of the potential for catastrophic environmental damage from offshore oil exploration and the critical need for robust safety regulations and responsible environmental stewardship in the energy industry.