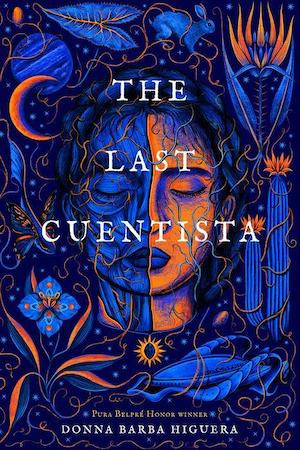

My journey into storytelling, culminating in my book, The Last Cuentista, often sparks questions about its unique blend of Mexican Folklore and science fiction. To some, this combination might seem unusual, but for me, these two worlds have always been intertwined, creating a rich tapestry of imagination.

My fascination with science fiction ignited in the glow of black and white television. Family gatherings were synonymous with mountains of delicious food and the captivating narratives of Rod Serling in Twilight Zone marathons. Having watched every episode countless times, we’d eagerly anticipate and shout out iconic lines like, “That’s not fair. That’s not fair at all. There was time now. There was, was all the time I needed…” or the startling reveal, “It’s a cookbook!” Science fiction, in its imaginative and thought-provoking nature, quickly became a comforting and familiar space for me.

This love affair with science fiction deepened with iconic series like Star Trek TOS and The Next Generation, and I’m now thrilled to be introducing a new generation to the wonders of Doctor Who.

However, my literary horizons truly expanded when my school librarian placed A Wrinkle in Time into my hands. From Madeleine L’Engle, I ventured into the works of Ursula K. Le Guin and Ray Bradbury, each author shaping my understanding of narrative and possibility. Yet, despite the profound impact of these books, they lacked a certain element – characters that mirrored my own experiences and cultural background.

These missing pieces weren’t absent from my life, however. They lived vibrantly in the stories shared around our kitchen table. My grandmother and aunt, keepers of our heritage, would recount captivating Mexican love stories with poignant endings, cautionary tales designed to guide us, and epic folklore passed down through generations, echoing through time.

I vividly remember being captivated by the haunting love story of Popocatépetl and Itzaccíhuatl, affectionately known as Popo and Itza. This legend, rooted in pre-colonial Mexico, tells of Popo, a valiant warrior deeply in love with Itza, the chieftain’s daughter. Seeking her hand in marriage, Popo was tasked by the chieftain to prove his worth by fighting in a war and returning victorious. Popo eagerly accepted this challenge, willing to risk his life for his beloved Itza.

In the version I grew up hearing, a jealous rival, fueled by envy, deceitfully informed Itza that Popo had perished in battle. Heartbroken by this false news, Itzaccíhuatl succumbed to grief and passed away. Upon his triumphant return, Popo was devastated to find his beloved Itza gone. In his sorrow, he carried her body to a snowy mountaintop, where he built a tomb, lit a torch, and joined her in death. The gods, witnessing their tragic love, transformed them into majestic volcanoes, Popocatépetl and Itzaccíhuatl, forever watching over Mexico City, a poignant reminder of enduring love and loss.

Other well-known legends in Mexican folklore carry a darker, more chilling essence. La Llorona, the weeping woman, is perhaps one of the most recognized figures, even beyond Mexican culture. This spectral figure is said to snatch away or drown those who wander near rivers after nightfall. Folklore varies depending on the region of Mexico and even extends north of the border, but the common thread identifies La Llorona as an indigenous woman who fell in love with a Spaniard. Their union was often forbidden, and in many versions, the Spaniard either abandoned her or married a Spanish woman. Consumed by despair, La Llorona tragically drowned their children in a river. Condemned to an eternal purgatory of inconsolable grief, she endlessly searches for her lost children. While traditionally associated with rivers, the reach of La Llorona’s legend extends far beyond waterways. Mexican grandmothers, mothers, aunts, and uncles skillfully adapt the tale to their surroundings, convincing children that La Llorona can also roam the desert, ready to take any child out past bedtime as a replacement for her own.

However, the legend that truly instilled fear in my childhood was that of El Cucuy. El Cucuy is the Mexican equivalent of the boogeyman, yet far more terrifying than its abstract American counterpart. He is depicted as a monstrous being, hairy and foul-smelling, with bloody claws, sharp fangs, and glowing eyes – a truly demonic cryptid. For a time, I was convinced El Cucuy resided in the small, unused room at my grandmother’s house. With a sweet smile, she would warn, “Go to sleep, or El Cucuy will come and eat you,” before gently closing the bedroom door. This tactic, while intended to encourage obedience, often backfired, leaving me wide awake with fear. Despite the fright, threats of El Cucuy or La Llorona are deeply ingrained in Mexican culture, serving as legendary disciplinary tools accepted by children without question, a testament to the power of folklore in shaping behavior.

Mexican folklore is not confined to just scary stories or bedtime tales used for discipline. Magical realism and folktales are interwoven into the fabric of everyday Mexican life. Even minor injuries were addressed with a touch of folk magic. A simple stubbed toe wouldn’t heal properly without my grandmother rubbing my foot and chanting the magical rhyme about a frog’s tail: “Sana sana colita de rana. Si no sana hoy, sanará mañana.” (Heal, heal, little frog tail. If it doesn’t heal today, it will heal tomorrow.) As a child, I wholeheartedly believed in the power of these words and the magic they held.

When I began writing, incorporating Mexican folklore and mythology into my science fiction novel wasn’t a conscious decision, but rather an organic emergence. A lifetime of these stories, these cultural touchstones, subtly guided my pen, inviting themselves into The Last Cuentista. Some of these narratives surfaced from the deepest recesses of my mind, leaving me to wonder if they were entirely fictional or rooted in some forgotten reality. My research revealed that they were, in fact, connected to “original versions,” some even tracing back to Spain. Yet, as is the nature of folklore, stories evolve with each telling, taking on the unique voice of the storyteller and the spirit of the places and people they encounter. As these tales journeyed across Mexico, adapting to different regions, cities, towns, and villages, they were imbued with local nuances and perspectives. The versions I heard were likely shaped by the experiences of generations before me, who migrated from Mexico to the U.S. and navigated a new world.

The tale of Blancaflor serves as a perfect illustration of this evolution. Originating in Spain, the story of Blancaflor has transformed over centuries and across continents. Like the threats of monsters and weeping women, promises of a Blancaflor story were used to entice children to bed, a reward for good behavior. Blancaflor is a narrative that storytellers have embellished and expanded upon over time, resulting in countless variations as diverse as the regions of Mexico where it has traveled and taken root.

With each retelling, details are subtly altered, nuances are lost or added, and characters may even transform. In the version of Blancaflor (meaning “white flower”) I was told, she was depicted with milky skin and golden hair, reflecting European beauty standards that permeated even Mexican folklore. The story unfolds with a prince embarking on a perilous mission to save his father’s life. His journey leads him to a forbidden realm ruled by an evil king, who sets him three impossible tasks to complete under threat of death. Despairing at the impossibility of the tasks, the prince is on the verge of giving up when Blancaflor, the king’s daughter, intervenes as a rescuer. She uses her magical abilities to assist the prince in accomplishing the seemingly impossible feats. As a reward, the king deceitfully offers the prince Blancaflor’s hand in marriage, but Blancaflor, wise to her father’s treachery, orchestrates their escape. She instructs the prince to steal the fastest horse, but he mistakenly chooses a slow, decrepit one. Blancaflor, with her magic, then grants extraordinary speed to the old horse. As she predicted, the king pursues them, intent on preventing their escape. In the version I heard, they successfully reach the prince’s kingdom, where they rule together, Blancaflor by his side.

In The Last Cuentista, I reimagined the Blancaflor story through the eyes of Petra, my protagonist and storyteller. Petra makes the tale her own, drawing inspiration from her surroundings on the spaceship Sagan, en route to a new planet. She personalizes the details and characters to mirror her own life journey. In Petra’s version, Blancaflor’s skin is brown, reflecting a shift towards greater representation. Blancaflor remains the more capable and resourceful character compared to the prince. The antagonist is no longer the stereotypical evil king but a sadistic woman with iridescent skin, mirroring Petra’s nemesis on the ship. Crucially, Petra subverts the traditional narrative by ensuring Blancaflor is not merely a prize in marriage. Instead, upon their arrival in the prince’s kingdom, the prince’s father recognizes Blancaflor’s superior leadership qualities and appoints her as his heir and the next ruler, with the prince taking on a supportive role as a consultant.

The way common stories evolve into unique family heirlooms is a vital aspect of my deep love for storytelling. This transformative power of narrative is what I aimed to capture in The Last Cuentista. As the storyteller, Petra embodies the agency to shape and reshape the stories she cherishes from her culture, allowing them to blossom and resonate with the complex events in her own life. For me, one of those formative events was growing up Latina in a town where the KKK still maintained a presence. For Petra, it’s the extraordinary journey across the stars, the profound loss of family, and the daunting challenge of facing an enemy determined to erase all memory of Earth.

Both the ancient echoes of folklore and the fresh narratives of modern experiences reside within me, fueling my creative spirit. Now, it is my turn to take these stories, make them uniquely my own, and pass them on to the next generation, ensuring their continued evolution and relevance.

In researching Mexican science fiction, I discovered that the genre, while rich in potential, is still relatively sparse in published works. Cosmos Latinos: An Anthology of Science Fiction from Latin America and Spain offered a valuable collection of short stories, originally written in Spanish and translated into English, published in 2003. However, it included only a limited number of works from Mexican writers, spanning over a century and a half.

Therefore, I was incredibly excited to learn about the release of Reclaim the Stars, a groundbreaking anthology of short stories by Latinx writers, compiled and edited by Zoraida Córdova, released by St. Martin’s Press in February 2022. This anthology has been on my highly anticipated list, representing a significant step forward for Latinx voices in science fiction.

Among Mexican-American writers who beautifully blend Mexican mythology and folklore with science fiction, David Bowles stands out. His graphic novel, The Witch Owl Parliament, illustrated by Raúl the Third and published by Tu Books (Lee and Low) in both Spanish and English, is a brilliant fusion of steampunk, religious undertones, magic, and science fiction. This graphic novel is truly unique. It opens with a Lechuza (owl) depicted as an owl-witch! This immediately resonated with me, evoking a vague childhood memory of a cautionary tale: “An owl in your house is actually una bruja (a witch), and she is coming to steal your soul!” Variations of this chilling folklore about the horror a Lechuza can inflict exist across Mexico and the Southwest. Bowles masterfully taps into this cultural fear, placing readers on edge from the very beginning. In The Witch Owl Parliament, lechuzas attack the main character, Cristina, a curandera, or healer, deeply connected to earth and nature, who uses folk magic to aid others. To save her, her well-meaning brother employs alchemy, ancient magic, and steampunk robotic innovation, transforming her into a cyborg. In a clever twist on her curandera identity, she becomes a powerful hybrid of healing, green magic, and warrior prowess. Growing up in a border town, David Bowles undoubtedly absorbed Mexican folklore and urban legends, which organically led to the captivating blend of lechuzas, magic, shapeshifters, and real-life curanderas in his steampunk graphic novel.

J.C. Cervantes, in her The Storm Runner series (Disney-Hyperion), draws inspiration from Mayan mythology. Her main character, Zane, is thrust into a magical world infused with tales of Ah Puch, the Mayan god of death, darkness, and destruction. Ah Puch, a skeletal deity capable of unleashing chaos, serves as a potent source of tension in this action-packed series. Similar to my own experience, J.C. Cervantes’ writing is heavily influenced by stories passed down from her grandmother. She states, “Magical realism is so integral to Mexican culture, most don’t question its magic or mysticism.” One example of this, deeply ingrained in J.C.’s upbringing, is the belief in a powerful lineage of women in her family, with power passed down through generations. This concept is woven into her upcoming YA book, Flirting with Fate (April 2022), where women can bestow blessings upon their descendants on their deathbeds. J.C. explains, “this idea that death is sacred opens a door to the enigmatic. And this comes from Mexican culture where death is celebrated differently.”

We need look no further than Día de los Muertos (Day of the Dead) to understand this unique cultural perspective on death. While many in American culture might perceive skeletal representations of humans (calacas) as macabre or frightening, in Mexican culture, they are embraced as vibrant and celebratory symbols. Día de los Muertos is a colorful holiday where death is not feared but rather intertwined with joy and cherished memories of loved ones who have passed.

As writers, sharing deeply personal aspects of ourselves and our culture can feel vulnerable. For me, writing The Last Cuentista was the most exposed I’ve ever felt creatively. The two elements I was once hesitant to share – my love for science fiction and Mexican folklore – are at the very heart of this book. I questioned how it would be received, wondering if this fusion would resonate with others or even make sense. But then I thought of my grandmother, and how she, as a storyteller, made every story her own, imbuing it with her unique spirit and perspective. Suddenly, within the pages of The Last Cuentista, I found myself back in that familiar, comforting treehouse of trust, where stories could freely unfold.

Now, I would love to hear from you. Would you share the folklore, mythology, and magical cautionary tales that were told to you by your grandparents, aunts, uncles, or cousins? Would you pass them on to others? As more of us weave our own cultural heritage and family experiences into our narratives, whether in science fiction or any other genre, whether through written words or stories shared around a fire, we create connections and understanding. This is the profound gift that stories offer us – the power to bridge divides and unite us through shared human experiences.

Donna Barba Higuera grew up in Central California and currently resides in the Pacific Northwest. Throughout her life, she has been captivated by the art of blending folklore with her personal experiences, weaving them into stories that ignite the imagination. Now, she channels this passion into writing picture books and novels. Donna’s debut book, Lupe Wong Won’t Dance, garnered a PNBA Book Award and a Pura Belpré Honor. The Last Cuentista is her critically acclaimed second novel.