For many seeking a connection to their heritage or simply an enriching cultural experience, the search term “Mexican Clubs Near Me” might spark curiosity. While this search could lead to vibrant nightclubs celebrating Mexican music and dance, it also opens a door to a deeper, more historical understanding of Mexican community building in the United States. This exploration reveals a fascinating history of Mexican social clubs, organizations formed by migrants that have profoundly shaped communities both in the U.S. and Mexico.

The story begins in 1962, when a group of Mexican migrants residing in Los Angeles conceived an initiative to support elderly residents in their hometown of Guadalupe Victoria, a small rancho nestled in north-central Mexico. Driven by a desire to give back, these individuals established Club Social Guadalupe Victoria.

Image: Ana Raquel Minian, Stanford historian, whose research sheds light on the impact of Mexican migrant clubs.

Over the subsequent two decades, Club Social Guadalupe Victoria became a powerful force for development in their hometown. Through dedicated fundraising efforts, they provided essential resources to construct a local clinic, build a fence for the school, establish electric power lines, ensure access to clean drinking water, and even restore the town’s cherished church.

This remarkable story of community action is brought to light by Stanford Assistant Professor of history Ana Raquel Minian. In a compelling article published in the Journal of American History, Minian delves into the origins and evolution of groups like Club Social Guadalupe Victoria. Her research unveils how these migrant associations flourished and effectively transformed entire towns in Mexico between the 1960s and 1980s.

Today, the legacy of these early clubs resonates. Hundreds of Mexican clubs and associations thrive across the United States, wielding considerable social and even political influence within Mexican communities and extending their reach back to their places of origin.

“It’s a common assumption that immigrants gradually lose ties with their home communities,” Minian explains. “However, these Mexican migrants demonstrably maintained strong, enduring connections with their hometowns, forging a dynamic community life that transcended borders.”

The Rise of Transnational Activism: Mexican Mutual Aid Societies

The tradition of mutual aid among Mexican migrants and U.S.-born Mexicans dates back to the 19th century. However, the 1960s, a period of heightened social activism across the United States, marked a turning point. It was during this era, particularly in East Los Angeles, that Mexican migrants began to form organizations with a focused mission: to directly support their hometowns in Mexico.

Club Social San Vicente symbol

Club Social San Vicente symbol

Image: Logo of Club Social San Vicente from 1967, embodying the spirit of community effort.

Club Social Guadalupe Victoria pioneered fundraising strategies centered around community gatherings. Small parties and picnics became avenues for raising funds, with each event generating between $200 and $1,000, according to Minian’s research. Word of the club’s success spread rapidly among migrants from other Mexican communities, inspiring them to establish their own hometown associations. By the late 1960s, the Boyle Heights neighborhood of Los Angeles became a hub for this movement, hosting at least 20 such clubs. Fundraising parties became significant social events, attracting hundreds of attendees, and club representatives in Mexico ensured that the collected funds reached those in need.

These clubs fostered a uniquely inclusive environment. They brought together individuals from diverse socioeconomic backgrounds, blurring distinctions between documented and undocumented workers in their shared purpose of community upliftment.

Minian emphasizes the significance of this self-organized movement: “The capacity of migrants to organize themselves and channel resources to Mexico gave rise to a powerful and innovative movement of transnational welfare activism. Through their collective actions, these clubs effectively assumed certain responsibilities often associated with the Mexican government, essentially becoming a form of extraterritorial welfare system.”

Navigating Challenges and Achieving Influence

The endeavors of these migrant clubs were not without obstacles. They encountered complexities in their interactions with Mexican officials at various levels of government. While some local municipalities collaborated with the clubs to facilitate specific projects, state and federal government entities often remained indifferent. Furthermore, instances of corruption emerged, with some officials demanding bribes to allow the cross-border transportation of aid.

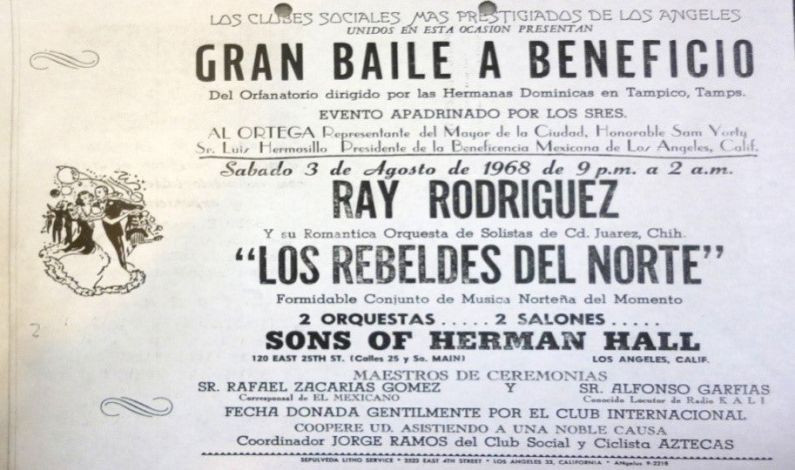

Poster advertising dance

Poster advertising dance

Image: A vintage poster from 1968 advertising a benefit dance, showcasing the vibrant social fundraising efforts of Mexican clubs in Los Angeles.

Despite these challenges, the social clubs persevered and gradually earned considerable respect and influence among Mexican residents. This growing social capital enabled them to exert pressure on the Mexican government to acknowledge and support their initiatives.

Minian notes a turning point: “By the mid-1980s, the scale of migrants’ investments in Mexico had become impossible for the Mexican government to ignore.”

Recognizing the political potential of these organized migrant communities, Mexican politicians began to seek their support. A notable example is Genaro Borrego Estrada, who, during his campaign for governor of Zacatecas state in 1986, actively courted migrant clubs in Los Angeles to bolster his popularity. Subsequently, he pioneered a program where the state government matched every dollar contributed by migrants to community development projects in Zacatecas.

This initial matching program has evolved significantly. Today, the Mexican government contributes three dollars for every dollar donated by migrants, and increasingly plays a role in directing how these funds are invested.

Uncovering the history of these impactful clubs presented research hurdles for Minian. Systematic record-keeping was not always a priority for either the migrant clubs or the recipient communities in Mexico. However, Minian’s persistence led her to valuable archives discovered in the unlikeliest of places: closets at La Casa del Mexicano, a cultural center in Boyle Heights, which served as an early meeting point for club organizers.

Minian’s research journey extended beyond archival discoveries. She embarked on months of bus travel through small towns in Zacatecas, ultimately locating Gregorio Castillas, a co-founder of Club Social Guadalupe Victoria. Through oral history interviews with Castillas and other migrants involved in the club movement, she gained invaluable firsthand accounts and perspectives.

Minian’s work provides a crucial counter-narrative to common stereotypes: “This research challenges the frequent portrayal of Mexicans solely as individuals seeking to immigrate to the United States to access its welfare system. In reality, these migrants actively avoided reliance on state resources. Instead, they established their own welfare organizations and proactively sent resources back to Mexico, with the ultimate aspiration of creating conditions that would allow other Mexicans to remain in their homeland and build economically stable lives.”

For those interested in “mexican clubs near me” today, understanding this rich history adds depth to the search. While you might find vibrant nightclubs, remember also the enduring legacy of Mexican social clubs – organizations built on community, mutual support, and a powerful desire to connect across borders. These historical clubs laid the groundwork for the dynamic Mexican communities and associations that continue to thrive in the U.S., offering avenues for cultural connection and community engagement for generations.