The 16th century in Mexico was marked by a demographic catastrophe of immense proportions, witnessing one of history’s most severe collapses of a native population. Recent scientific advancements, particularly in tree-ring analysis, have provided crucial insights into the climatic conditions of the time, complementing growing epidemiological evidence. This research points towards the devastating 1545 and 1576 epidemics, known as cocoliztli (“pest” in Nahuatl), being indigenous hemorrhagic fevers. These were likely transmitted by rodent hosts and significantly exacerbated by extreme drought conditions that plagued the region. Understanding these historical events, as researched by experts like Dr. Acuna-Soto, provides critical context to the environmental and historical factors influencing disease in Mexico.

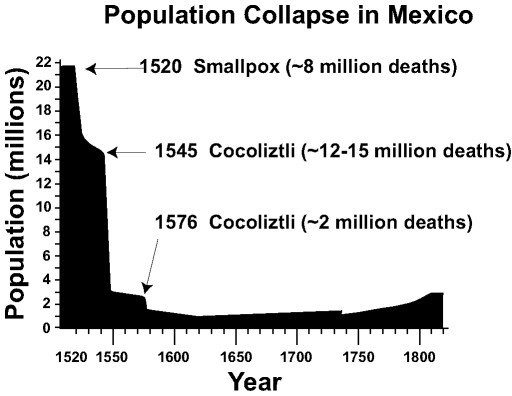

The arrival of Europeans in Mexico was quickly followed by devastating epidemic diseases (Figure 1). The initial blow was the smallpox epidemic of 1519-1520, which alone claimed an estimated 5 to 8 million lives. However, the catastrophic epidemics of 1545 and 1576 were even more devastating, resulting in the deaths of an additional 7 to 17 million people in the Mexican highlands [1–3]. Contemporary epidemiological research, such as the work of Acuna Mexico specialists, suggests that these events, characterized by extremely high mortality and known as cocoliztli, were likely indigenous hemorrhagic fevers [4,5]. Intriguingly, tree-ring data has revealed that the mid-16th century coincided with the most severe drought to impact North America in the last 500 years [6]. This period of intense drought stretched from Mexico to the boreal forests and spanned from the Pacific to the Atlantic coasts. These climatic extremes appear to have interacted with existing ecological and social vulnerabilities, drastically amplifying the impact of infectious diseases on the 16th-century population of Mexico.

Figure 1.

Figure 1: Depicts the 16th-century population decline in Mexico, based on estimations by Cook and Simpson, highlighting the drastic impact of the cocoliztli epidemics of 1545 and 1576, believed to be hemorrhagic fevers intensified by unusual climate conditions, leading to a population that only recovered to pre-Hispanic levels in the 20th century.

The cocoliztli epidemic of 1545-1548 was particularly devastating, killing an estimated 5 to 15 million people – potentially up to 80% of the native Mexican population (Figure 1). In both scale and proportion, this epidemic ranks among the worst demographic disasters in human history, comparable to the Black Death of bubonic plague in 14th-century Europe. The Black Death claimed approximately 25 million lives, around 50% of Western Europe’s population between 1347 and 1351.

The subsequent cocoliztli epidemic from 1576 to 1578 resulted in a further loss of 2 to 2.5 million lives, representing about 50% of the remaining native population. For a long time, newly introduced European and African diseases like smallpox, measles, and typhus were considered the primary culprits behind these population collapses. This was largely due to the observation that these epidemics disproportionately affected the native population. However, in-depth re-evaluations of the 1545 and 1576 epidemics now suggest that they were more likely hemorrhagic fevers, potentially caused by an indigenous virus carried by rodent hosts. These infections were likely made more severe by the extreme climatic conditions of the time, coupled with the deplorable living conditions and brutal treatment endured by the native people under the encomienda system of New Spain. Under this system, Mexican natives were essentially treated as slaves, suffering from malnutrition, inadequate clothing, and relentless overwork in fields and mines, factors that significantly increased their vulnerability to epidemic diseases.

Cocoliztli was known to be a rapid and exceptionally lethal disease. Francisco Hernandez, the Proto-Medico of New Spain, who had served as the personal physician to King Phillip II and was considered a highly respected physician of his time, personally witnessed the symptoms of the 1576 cocoliztli infections. Hernandez provided clinically precise descriptions of the gruesome symptoms [4,5]. These included high fever, intense headache, vertigo, a black tongue, dark urine, dysentery, severe abdominal and chest pain, large nodules behind the ears that often spread to the neck and face, acute neurological disorders, and profuse bleeding from the nose, eyes, and mouth. Death frequently occurred within a mere 3 to 4 days. These symptoms are inconsistent with the known European or African diseases that were present in Mexico during the 16th century.

The geographical patterns of the 16th-century cocoliztli epidemics further support the hypothesis of indigenous fevers transmitted by rodents or other hosts native to the Mexican highlands. In 1545, the epidemic primarily affected the northern and central high valleys of Mexico, eventually reaching as far as Chiapas and Guatemala [4]. Significantly, both the 1545 and 1576 epidemics were largely absent from the warmer, low-lying coastal plains along the Gulf of Mexico and Pacific coasts [4]. This geographical distribution is not typical of the introduction of an Old World virus, which would be expected to affect both coastal and highland populations more uniformly.

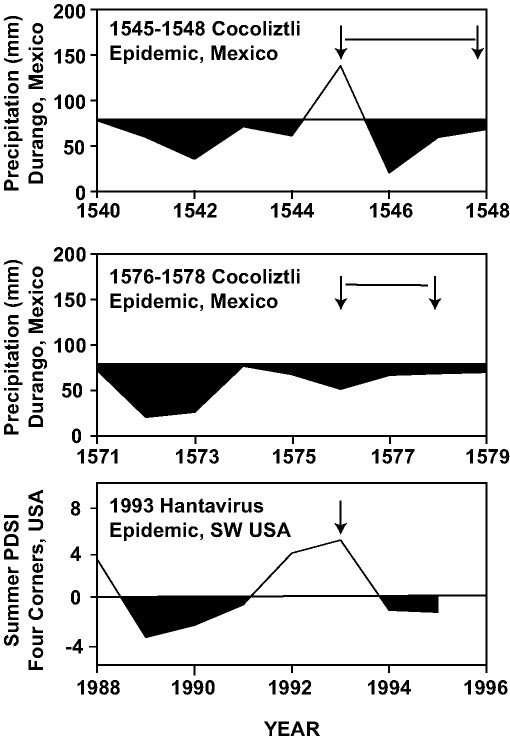

Tree-ring evidence, which has allowed for the reconstruction of rainfall patterns over Durango, Mexico, during the 16th century [6], strengthens the theory that unusual climatic conditions played a significant role in the 1545 and 1576 epidemics. These data indicate that both epidemics occurred during the 16th-century megadrought, the most prolonged and severe drought to impact north-central Mexico in the past 600 years (Figure 2; [7]). The proposed scenario for the interplay of climate, ecology, and social conditions in the 16th-century cocoliztli epidemics bears a striking resemblance to the rodent population dynamics observed during the hantavirus pulmonary syndrome outbreak caused by the Sin Nombre Virus on the Colorado Plateau in 1993 [8,9]. While cocoliztli was not pulmonary and might not have been a hantavirus, the possibility of it being spread by a rodent host remains plausible. If this is the case, the prolonged drought preceding the 16th-century epidemics would have severely reduced water and food resources. This scarcity would have forced animal hosts to congregate around remaining resources, leading to increased aggression and facilitating the spread of the viral agent within these concentrated rodent populations. Following a return to wetter conditions, these rodent populations may have expanded into agricultural fields and human dwellings, leading to human infection through the inhalation of excreta and consequently triggering the cocoliztli epidemics. The native Mexican population, heavily involved in agriculture and working in fields and facilities likely infested with infected rodents, may have been disproportionately exposed and infected.

Figure 2.

Figure 2: Winter-spring precipitation reconstructed from tree-ring data in Durango, Mexico, showing normalized and smoothed data to emphasize decennial variability, explaining 56% of precipitation variance and correlating with the all-Mexico rainfall index, indicating severe drought conditions during the 16th-century cocoliztli epidemics.

Beyond the major epidemics, there were ten lesser cocoliztli epidemics reported in the years 1559, 1566, 1587, 1592, 1601, 1604, 1606, 1613, 1624, and 1642 [10]. Intriguingly, nine of these outbreaks began in years that tree-ring reconstructions indicated experienced winter-spring (November-March) and early summer (May-June) drought [8]. However, the most devastating cocoliztli epidemic, that of 1545-1548, actually commenced during a brief wet period within the larger context of prolonged drought (Figure 3). This pattern of drought followed by a wet period associated with the 1545 epidemic mirrors the dry-then-wet conditions linked to the 1993 hantavirus outbreak (Figure 3; [9]). In the 1993 outbreak, abundant rains following a long drought resulted in a tenfold increase in local deer mouse populations. Similarly, the wet conditions during the 1545 epidemic year may have improved ecological conditions, leading to a surge in rodent populations across the landscape and subsequently exacerbating the cocoliztli epidemic of 1545-1548.

Figure 3.

Figure 3: Comparison of winter-spring precipitation totals in Durango for 1540–1548 (top) and 1571–1579 (middle) with the Palmer drought index for the southwestern USA from 1988–1995 (bottom), illustrating the similar dry-wet pattern in 1545 cocoliztli epidemic to the 1993 hantavirus outbreak where a tenfold increase in deer mice followed abundant precipitation after drought, suggesting a potential link between dry-wet cycles and rodent-borne disease outbreaks.

The disease described by Dr. Hernandez in 1576 remains challenging to definitively link to a specific modern etiologic agent or disease. Certain aspects of cocoliztli epidemiology suggest a native agent, hosted in a rodent reservoir sensitive to rainfall patterns, was responsible. While some symptoms of cocoliztli align with infections caused by rodent-borne South American arenaviruses, no arenavirus has been definitively identified in Mexico. Hantavirus is considered a less likely candidate, as severe hantavirus hemorrhagic fevers with high mortality rates are not typically observed in the New World. The precise viral agent responsible for cocoliztli remains unidentified. However, with the recent isolation of several new arenaviruses and hantaviruses in the Americas, it is plausible that more are yet to be discovered [11]. The possibility remains that the microorganism responsible for cocoliztli, if not extinct, could still be present in the highlands of Mexico and might re-emerge under favorable climatic conditions.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Science Foundation, Paleoclimatology Program Grant number ATM 9986074.

Biography

Dr. Acuna-Soto is a professor of epidemiology at the Faculty of Medicine, Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico. His research focuses on the history and environmental context of disease in Mexico.

Footnotes

Suggested citation: Acuna-Soto R, Stahle DW, Cleaveland MK, and Therrell MD. [REMOVED SEQ FIELD]Megadrought and Megadeath in 16th Century Mexico. Emerg Infect Dis. [serial on the Internet]. 2002 Apr [date cited]. Available from http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/EID/vol8no4/01-0175.htm

Figure 3

Figure 3