The Mexico City Earthquake of 1985 stands as a stark reminder of the raw power of nature and the vulnerability of even the most vibrant metropolises. On the morning of September 19, 1985, at 7:18 am local time, a magnitude 8.0 earthquake struck off the coast of Michoacán, Mexico, unleashing catastrophic devastation upon Mexico’s capital, Mexico City, and leaving an indelible mark on the nation’s history. This seismic event, also referred to as the Michoacán earthquake, not only caused widespread death and injury but also exposed critical vulnerabilities in the city’s infrastructure and disaster preparedness.

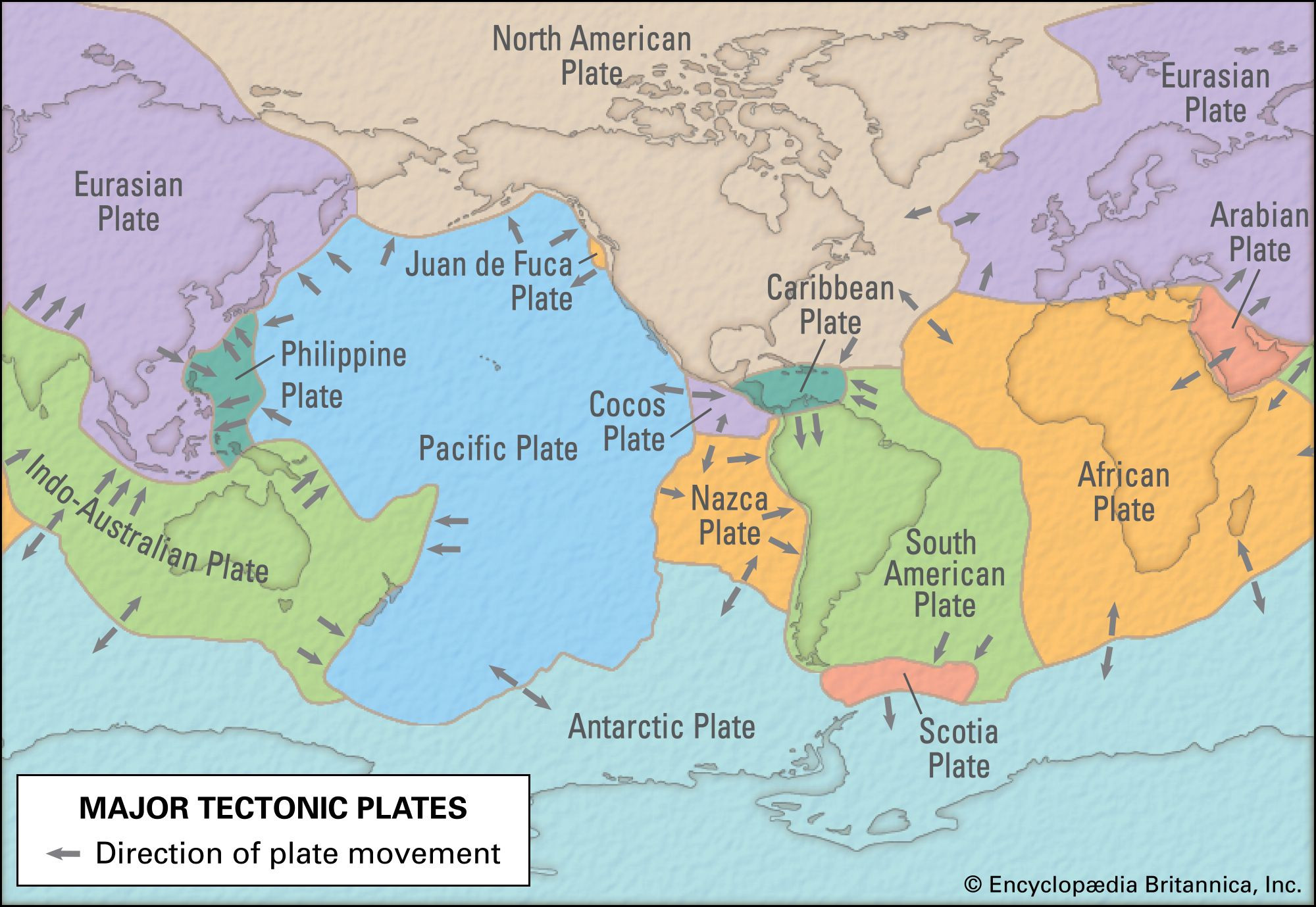

The earthquake’s epicentre was located in a seismically active zone off the coast of Michoacán, approximately 200 miles (320 km) from Mexico City. This region is characterized by the tectonic tension between the North American Plate and the subducting Cocos Plate, a major fault line known as the Middle America Trench, part of the volatile Circum-Pacific Belt, or Ring of Fire. Geologists had identified this specific area as the Michoacán seismic gap, noting the accumulation of seismic energy since a 1911 earthquake, with smaller tremors occurring on either side in the 1970s, foreshadowing a potentially larger event. Adding to the complexity, a significant aftershock, nearly equal in magnitude to the initial quake, struck the following evening southeast of the first epicenter, compounding the disaster.

While the states of Michoacán and Jalisco experienced considerable damage, with Ciudad Guzmán in Jalisco seeing nearly 600 adobe houses reduced to rubble, Mexico City bore the brunt of the earthquake’s fury. The unique and precarious topography of Mexico City significantly amplified the earthquake’s destructive power. Built on the drained bed of Lake Texcoco, the city’s central areas are characterized by loose, water-saturated lacustrine sediments. These soft soils dramatically amplified the seismic waves, causing ground motion in the city center to be up to five times stronger than in outlying areas with firmer ground. This phenomenon, known as soil amplification, turned the ground itself into a hazard.

Tectonic plates map illustrating the Cocos Plate subducting under the North American Plate, the cause of the 1985 Mexico City earthquake.

Tectonic plates map illustrating the Cocos Plate subducting under the North American Plate, the cause of the 1985 Mexico City earthquake.

Buildings between 5 and 15 stories in height proved particularly vulnerable. The seismic waves resonated with the natural frequency of these mid-rise structures, leading to a dangerous harmonic resonance that exacerbated swaying and structural stress. This resonance effect contributed significantly to the widespread collapse of over 400 buildings and damage to thousands more. The scenes across the city were of utter devastation, with buildings pancaked, streets filled with debris, and the air thick with dust and the sounds of sirens and cries for help.

The immediate aftermath of the Mexico City earthquake plunged the city into chaos. The earthquake severed power lines, crippling essential services. The capital was left without electricity, disrupting public transit and disabling traffic lights, leading to gridlock and further hindering rescue efforts. While power was partially restored the day after the initial shock, the subsequent aftershock that evening plunged the city back into darkness. The telephone system suffered critical damage, effectively cutting off communication within the city and with the outside world for days, isolating communities and impeding the coordination of aid. The government’s initial response was widely criticized. President Miguel de la Madrid and his administration were slow to implement the national emergency plan and initially declined international assistance. This hesitation was interpreted by some as politically motivated, fearing the military gaining prominence through rescue operations. However, facing the magnitude of the disaster, the government soon reversed course and accepted international aid coordinated by the United Nations, receiving crucial supplies and financial support from numerous countries.

In the crucial hours and days following the earthquake, the people of Mexico City demonstrated remarkable resilience and community spirit. Faced with government inaction, ordinary citizens took the lead in rescue and relief efforts. Neighbors and colleagues spontaneously organized to dig survivors from the rubble, provide first aid, and distribute essential supplies. Residents from less affected areas of the city flocked to the devastated central districts, particularly low-income neighborhoods, to offer assistance. This outpouring of citizen solidarity became a defining feature of the earthquake’s aftermath. While official figures estimated the death toll at 10,000, many journalists and eyewitnesses believed the actual number of fatalities was significantly higher. Tens of thousands more sustained injuries, overwhelming the city’s medical infrastructure, which itself had been severely damaged with several major hospitals rendered unusable. Approximately 250,000 people were left homeless, adding to the immense humanitarian crisis.

In the wake of the disaster, the damnificados, meaning “the damned” or the displaced, emerged as a powerful social and political force. These victims, alongside pre-existing grassroots organizations, coalesced into the Coordinadora Única de Damnificados (CUD). This unified body demanded that instead of relocating the displaced, the government should expropriate destroyed properties and construct new housing in the same locations. Facing immense public pressure and recognizing the crucial role of these community groups in the recovery, President De la Madrid’s government conceded to these demands. With financial assistance from the World Bank, nearly 100,000 homes were rebuilt or refurbished within two years. While the CUD dissolved in 1987 after achieving its primary goals, some constituent groups continued as the Asamblea de Barrios (Neighborhood Assembly), advocating for low-income housing rights. The 1985 Mexico City earthquake was a watershed moment, exposing vulnerabilities, highlighting the power of community action, and leading to significant changes in disaster preparedness and urban development in Mexico City. The earthquake remains a poignant chapter in the city’s story, a testament to both its fragility and its enduring spirit of resilience.