In the year 2000, deep within a mountain near Naica, Mexico, miners were in pursuit of new ore deposits when they stumbled upon a sight that defied expectations and ignited the imagination of the scientific world. Emerging into a horseshoe-shaped cave, they found themselves surrounded by colossal, milky-white crystals that seemed to pierce the very air around them. These weren’t just crystals; they were immense beams of gypsum, some stretching nearly 12 meters in length and a meter in width, radiating in all directions from the cave’s limestone embrace. Bathed in the beams of the miners’ lights, the Cave of Crystals, as it soon became known, revealed a hidden world of breathtaking beauty and profound scientific intrigue.

Awe-inspiring giant gypsum crystals in Mexico's Cave of Crystals dwarf a human figure, showcasing their immense size.

Awe-inspiring giant gypsum crystals in Mexico's Cave of Crystals dwarf a human figure, showcasing their immense size.

Nestled 290 meters beneath the surface, under a mountain rich in lead, zinc, and silver, Mexico’s Cave of Crystals immediately captivated researchers globally. Drawn by its otherworldly allure and the scientific mysteries it held, experts from various fields ventured into this subterranean chamber. Among them was Juan Manuel García-Ruiz, a crystallographer from the University of Granada, Spain. For García-Ruiz, who had dedicated years to growing crystals in laboratory settings since his youth, stepping into the Cave of Crystals was a pinnacle moment. He described his initial experience as euphoric, overwhelmed by the sheer scale and grandeur of the natural crystal formations.

Over the subsequent two decades, scientists, including García-Ruiz, have confronted the cave’s intensely challenging environment—marked by extreme heat and humidity—to unravel the secrets of the crystals’ origin and growth. Now, with many of the initial questions addressed, the focus has shifted towards safeguarding these magnificent formations for generations to come. The crucial question remains: can these natural wonders be preserved amidst the ongoing mining operations and the relentless forces of nature within the mountain?

Geological Genesis: How the Cave of Crystals Was Formed

The story of Mexico’s Cave of Crystals begins approximately 26 million years ago, when a significant upwelling of magma pushed through the Earth’s crust beneath what is now southeastern Chihuahua, Mexico. This powerful geological event gave rise to the mountain near Naica and, crucially, forced hot, mineral-rich waters into the caverns and fissures within the limestone rock. It was within these mineral-laden waters that the extraordinary genesis of the Naica crystals commenced.

The cave became a reservoir of water saturated with calcium sulfate. While calcium sulfate can crystallize into several mineral forms, in the Naica caves, gypsum (CaSO4·2H2O), specifically the transparent, colorless variety known as selenite, emerged as the dominant mineral.

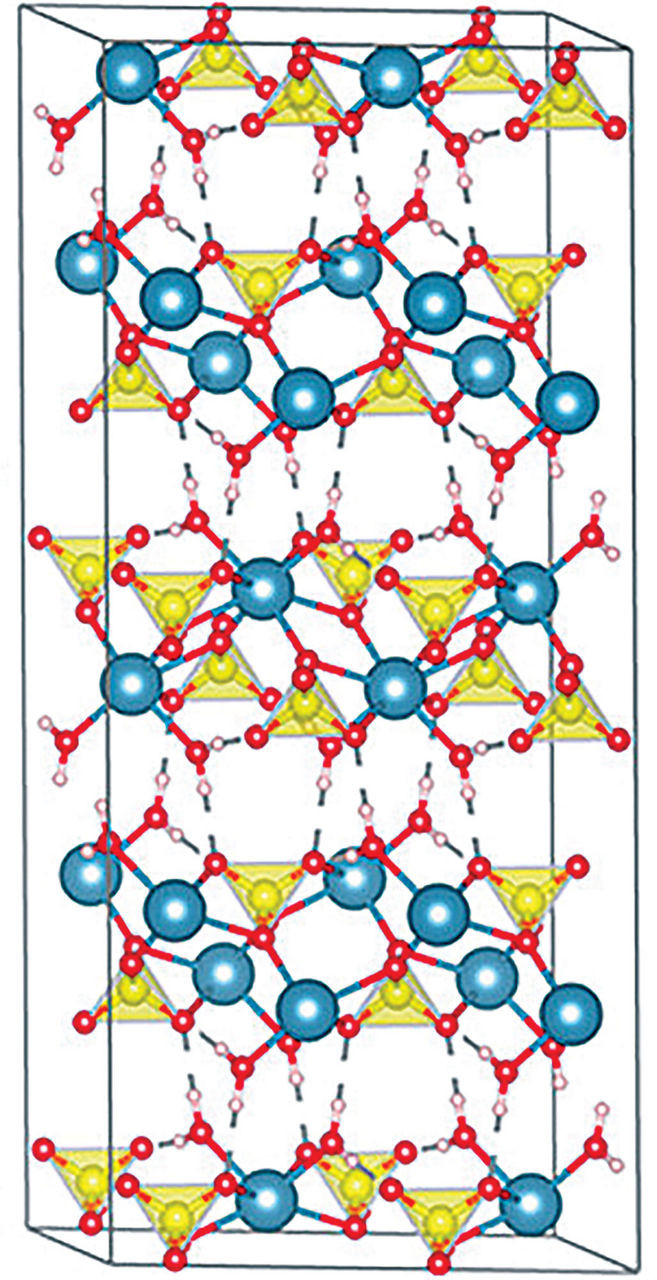

Detailed crystal structure of gypsum, highlighting the layers of calcium sulfate and water molecules, key to understanding crystal growth in Mexico's Cave of Crystals.

Detailed crystal structure of gypsum, highlighting the layers of calcium sulfate and water molecules, key to understanding crystal growth in Mexico's Cave of Crystals.

Gypsum’s crystal structure is characterized by layers of calcium sulfate molecules interleaved with double layers of water molecules. This structure plays a vital role in its formation and growth. As Alexander Van Driessche, a crystallographer from the National Center for Scientific Research’s Institute of Earth Science, explains, mineral stability is temperature-dependent. Anhydrite (CaSO4), another form of calcium sulfate, is more stable at temperatures above roughly 58 °C, while gypsum is more stable—and less soluble—below this temperature.

Initially, in the hot, magma-heated waters, anhydrite deposits began to form. Over millennia, as the water gradually cooled, a critical shift occurred. When the temperature dipped below 58 °C, the anhydrite started to dissolve. This dissolution process released calcium and sulfate into the water, creating a solution that was just barely supersaturated with these minerals. These conditions were ideal for the nucleation and slow growth of gypsum crystals (Geology 2007, DOI: 10.1130/G23393A.1).

The Secret to Gigantic Growth: Time and Perfect Conditions

Crystal formation, whether in a laboratory or a natural cave, invariably begins with nucleation. This is the process where the molecular building blocks of a crystal arrange themselves around a minute, foundational structure and initiate growth. Consider snowflakes, which nucleate around tiny particles in the atmosphere before falling to earth. In solutions containing ions, high supersaturation levels typically lead to the nucleation of many crystals, while low supersaturation promotes fewer nucleation sites but allows for more substantial crystal growth. The Cave of Crystals presented a unique scenario: conditions were perfectly poised to limit nucleation while fostering exceptional growth for the few crystals that did form.

Driven by the awe-inspiring scale of the Naica crystals, Van Driessche and his colleagues embarked on laboratory investigations into gypsum nucleation. Their research revealed a surprising mechanism: gypsum crystals originate from nanoclusters of CaSO4 that coalesce, rather than forming from a conventional tiny gypsum crystal seed, as previously assumed (Science 2012, DOI: 10.1126/science.1215648).

Related: Giant crystals grow superslowly

Understanding the fundamental processes of gypsum crystal formation has implications far beyond the caves of Mexico. It could provide insights for preventing unwanted mineral buildup in desalination plants or even explain gypsum formations observed on Mars. However, for Van Driessche and García-Ruiz, the quest extended beyond nucleation; they were determined to understand how the Naica beams attained their colossal dimensions.

Cave of Swords: A Tale of Contrasting Crystal Formation

The Cave of Crystals is not the only gypsum crystal cave beneath the mountain near Naica. The same mineral-rich waters permeated other subterranean chambers in the vicinity. However, the crystals in these neighboring caves did not achieve the same mind-boggling size. Van Driessche and García-Ruiz discovered that, alongside the Goldilocks conditions facilitating crystal formation, a precisely slow cooling rate was crucial for the mammoth proportions of the crystals in the Cave of Crystals.

Sword-like gypsum crystals densely packed in Mexico's Cave of Swords, contrasting with the giant crystals of the Cave of Crystals due to different cooling rates.

Sword-like gypsum crystals densely packed in Mexico's Cave of Swords, contrasting with the giant crystals of the Cave of Crystals due to different cooling rates.

The Cave of Swords, situated at a shallower depth of 120 meters within the mine, provides a striking contrast. As its name suggests, its walls are densely covered with shorter gypsum crystals, resembling medieval swords, reaching up to 2 meters in length. In the deeper Cave of Crystals, the water cooled at a considerably slower pace compared to the Cave of Swords. This gradual cooling over vast timescales meant that only a limited number of gypsum crystals nucleated in the Cave of Crystals, allowing them to grow to enormous sizes. Conversely, the faster temperature drop in the Cave of Swords favored nucleation, resulting in a multitude of smaller crystals. This difference vividly illustrates the delicate balance between crystal nucleation and growth, a “textbook example,” according to Van Driessche.

The extended period during which the water temperature in the Cave of Crystals remained within the transition zone between anhydrite and gypsum allowed the crystals to grow undisturbed and undiscovered for an immense duration. But precisely how long? This became the next key question for the researchers.

A Million Years in the Making: Dating the Crystal Giants

Determining the age of the crystals proved to be a complex challenge. Their exceptional purity meant that standard isotope-dating techniques, which rely on trace elements like uranium, could only offer rough estimates. Instead, armed with crystal and water samples from the Naica mine, Van Driessche, García-Ruiz, and their team meticulously measured crystal growth rates in the laboratory.

The layered structure of gypsum crystals—calcium sulfate layers sandwiching water molecule layers—simplified this task. The hydrogen bonds between water layers are easily broken, allowing thin flakes to be gently removed, providing pristine, flat surfaces ideal for growth studies, as Van Driessche explains.

When I entered the first time, after the first couple of minutes of stupor, I burst out laughing. I was euphoric.

Juan Manuel García-Ruiz, crystallographer, University of Granada

By immersing these pristine gypsum samples in water from the mine for 24–48 hours, the team measured minute increases in the height of the flat surface using phase-shifting interferometry, a light-based technique capable of detecting surface growth rates as slow as 10–5 nm/s. By conducting measurements across the temperature range relevant to crystal formation in the cave (approximately 54 to 58 °C), the scientists could estimate the growth rates of the Naica crystals under natural conditions. Using these rates, they calculated the time required for a 1-meter thick crystal beam to form at 55 °C.

The result was astonishing. Even with the understanding that crystal growth was exceptionally slow, the calculation revealed that such crystals would have taken nearly 1 million years to grow (Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2011, DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1105233108). This glacial pace equates to adding the thickness of a sheet of paper roughly every 200 years, according to Van Driessche.

A Fragile Paradise: Challenges of Preservation in a Harsh Environment

If the Cave of Crystals had remained submerged, the crystals might have continued to grow to even greater sizes. Current conditions within the cave are still conducive to gypsum crystal formation and growth, with a consistent water temperature of about 55 °C at that depth, notes Van Driessche. Small ponds within the mine even contain newly forming gypsum crystals. However, over years of mining operations in Naica, the water table has been artificially lowered to facilitate access to deeper lead, zinc, and silver deposits. While this drainage unveiled the giant crystals, it also created an extremely harsh environment and introduced new threats to the crystals themselves.

During active mining, Industrias Peñoles, the mining company, pumped water out of the mountain at a rate equivalent to filling an Olympic swimming pool every 40 minutes, creating a small artificial lake near Naica, as Van Driessche recounts. As the water level receded, more caves and tunnels were exposed to air and human access. The Cave of Crystals, due to its depth and relatively recent discovery, escaped the extensive looting that occurred in the shallower Cave of Swords, discovered in 1910, where many of the largest and most beautiful crystals were removed by collectors.

Peñoles implemented strict access controls to the Cave of Crystals to protect both the crystals and visitors. The cave’s environment pushes human physiology to its limits. Temperatures hover around 50 °C with over 90% relative humidity, rendering sweating ineffective for cooling.

I just want to see them once more.

María Elena Montero-Cabrera, researcher, Center for Research in Advanced Materials

Navigating the cave is also perilous, explains María Elena Montero-Cabrera, a researcher at the Center for Research in Advanced Materials in Chihuahua. Researchers had to carefully traverse gypsum spears slick with condensation to explore the cave. Extreme caution was necessary to avoid getting lost or falling, as rescue operations would be exceptionally challenging and dangerous.

The extreme conditions limited researchers’ stays in the cave to brief 10–15 minute intervals, according to Montero-Cabrera. The cave is sealed off from the rest of the mine by double doors, isolating the crystals and maintaining a more manageable temperature and humidity in the antechamber for human safety. Medical checks were mandatory before each entry to ensure visitors were fit to endure the cave’s climate.

These harsh conditions, while challenging for researchers, present different risks to the crystals. The largest beams, estimated to weigh 40–50 metric tons, are at risk of cracking under their own weight without the buoyant support of water. Gypsum is a soft mineral, rating only 2 on the Mohs hardness scale (talc is 1, diamond is 10). The passage of human feet has already visibly marked a darkened path into the crystals on the cave floor, notes Van Driessche.

Related: Giant crystals in Mexican cave face dehydration

To devise effective preservation strategies, Montero-Cabrera and her team in Chihuahua studied the impact of the drained environment on the crystal surfaces. In a year-long lab experiment, they exposed Naica crystal samples to various gaseous and liquid environments to identify potential threats to the gypsum’s long-term integrity and appearance.

Their findings indicated that the crystals fared slightly better in liquid environments, while gaseous environments posed a risk of dehydration. Specifically, they detected bassanite, a dehydrated form of calcium sulfate, on the surface of several gypsum crystals (Cryst. Growth Des. 2018, DOI: 10.1021/acs.cgd.8b00583). This suggests that the crystals’ appearance will gradually change over time. However, the research also clearly indicated that removing crystals from the sealed cave is not a viable preservation strategy, according to Montero-Cabrera.

The Future of the Cave and Lessons from Other Crystal Caves

Research activity in the Cave of Crystals has gradually decreased as many fundamental questions have been addressed. Mining operations closed access to the cave around 2015 due to a leak that flooded the mine faster than pumps could remove water. While water levels in the mine have risen, it remains unclear if the Cave of Crystals has been re-submerged.

Transparent gypsum crystals inside the geode of Pulpí, Spain, offering a comparison to the milky crystals of Mexico's Cave of Crystals and further research opportunities.

Transparent gypsum crystals inside the geode of Pulpí, Spain, offering a comparison to the milky crystals of Mexico's Cave of Crystals and further research opportunities.

Montero-Cabrera reports recent indications that mining may resume through a different entrance, potentially allowing researchers renewed access to the cave. Whether the cave itself will flood again remains uncertain. In the interim, researchers are exploring other captivating gypsum deposits worldwide to further their understanding of gypsum crystallization and growth.

Related: Gypsum genesis

For instance, García-Ruiz and Van Driessche are studying crystals discovered within an 8-meter long geode in Pulpí, southern Spain. While the Pulpí gypsum crystals are smaller, they are more transparent than those in Mexico’s Cave of Crystals, prompting the team to investigate the underlying reasons for these morphological differences. García-Ruiz also aims to refine his age estimates for the Naica crystals.

Although Montero-Cabrera has shifted her research focus, she eagerly anticipates the possibility of returning to the Cave of Crystals if it reopens. “I just want to see them once more,” she expresses.

Until then, the giant crystals remain isolated—a hidden, breathtaking spectacle awaiting an uncertain future deep within the Earth.