On June 2nd, Claudia Sheinbaum, the candidate from the ruling Morena party (Movimiento de Regeneración Nacional), won the presidential election with nearly 60% of the vote, making history as the first woman president of Mexico. Simultaneously with the presidential race, Mexican voters participated in legislative, state, and municipal elections. However, the electoral process was marred by violence, including assassinations and attacks targeting candidates and other political figures. ACLED (Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project) recorded over 330 incidents of violence against political figures during the campaign period, from the start of the federal campaign on March 1st to election day on June 2nd. Tragically, at least 95 of these incidents resulted in one or more deaths. The level of violence during this election campaign reached a historic high, surpassing the violence recorded in the 2018 general elections and the 2021 federal elections, which saw 254 and 257 events, respectively.

The heightened levels of violence during the 2024 campaign period also impacted candidates who were not direct targets of violent incidents. A staggering 553 candidates requested state protection after receiving threats,16 while others chose to withdraw from the race due to intimidation.17 Despite this alarming situation, none of the leading presidential candidates presented substantial proposals to address this critical issue of political violence.

This report delves into the main trends of the 2024 election cycle:18

- Violent attacks are predominantly concentrated at the local level: Over 80% of the 216 violent events targeting candidates, their supporters, or family members involved candidates running for local positions.

- Perpetrators relentlessly pressure local authorities: Current and former officials not seeking re-election were also targeted in over 40% of the violent events.

- Violence against political figures extends beyond the campaign period: While violence intensifies during the campaign, it begins to escalate early in the electoral cycle and persists well after election day.

- Competition among organized crime groups is a major driver of violence: Six of the ten states with the highest number of violent events against political figures are also among the ten most affected by organized crime violence, although there are notable exceptions.

- Competition among local power brokers also significantly fuels violence: Less violent forms of unrest, such as riots and property destruction, account for around 30% of the events, indicating that local power struggles, community grievances regarding process irregularities, and rejection of results, in addition to organized crime, can trigger violence against political figures.

Local Elections as Hotspots for Violence

Approximately 40% of violent events targeting political figures during the 2024 election cycle were directed at candidates vying for public office. While local, state, and federal elections were held on the same day, over 80% of the 216 violent incidents against candidates, their families, or supporters targeted political figures running for local positions, including mayoralties and municipal councils. The remaining 20% encompassed attacks against individuals running for federal positions and former candidates.

Veracruz provides a striking example of how local elections can fuel violence. Unlike most federal entities that held municipal elections in 2024, Veracruz will hold these elections in 2025. During the last municipal elections in 2021, Veracruz was the state with the highest level of violence against political figures, with 57 events recorded in the six months leading up to the vote and the two weeks following. However, this time ACLED recorded about a quarter of the 2021 figure—17 events—in Veracruz, dropping it to tenth place in the ranking (see chart below). This dramatic shift in violence levels underscores how the absence of municipal elections can correlate with lower levels of violence.

Violence targeting political figures in Mexican states between September 2023 and June 2024

Violence targeting political figures in Mexican states between September 2023 and June 2024

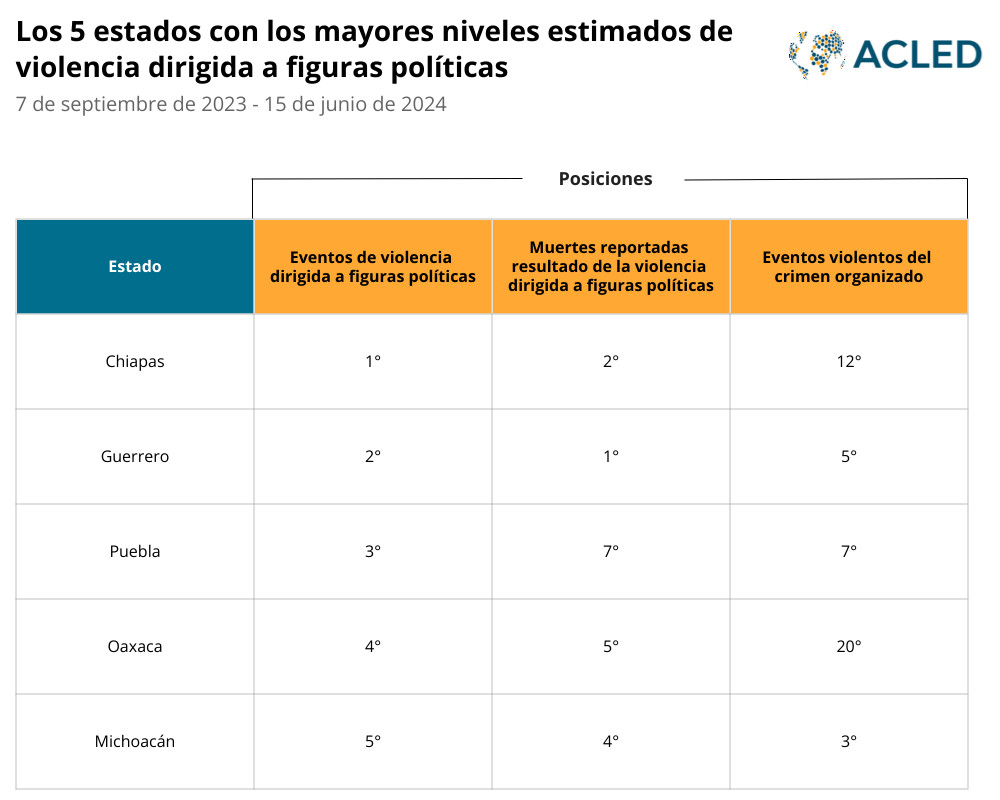

In other states, the holding of local elections also resulted in a high level of violence against officials, functionaries, and candidates due to intense competition for power, with a significant number of candidates running in local elections becoming targets for organized crime groups and political rivals. Candidates were particularly vulnerable in the states of Hidalgo, Mexico, Morelos, and Puebla, where they constituted the majority of victims. However, attacks against candidates were deadliest in the states of Chiapas and Guerrero, where 21 and 20 individuals, respectively, died in violent incidents involving candidates.

Although on a smaller scale, elections for state-level officials, such as governors and local deputies, also contributed to the violence. Several candidates for local congresses were targeted in this election cycle, particularly in states holding gubernatorial elections. In Chiapas and Morelos, armed men attacked two state senate candidates from the Fuerza y Corazón por México coalition, while in Veracruz, armed men fatally shot a MORENA candidate for local deputy. These instances indicate that while municipal elections are a major trigger for political violence, significant state-level contests can also contribute to the violence observed in 2024.

Of all incidents recorded since the start of the electoral process, at least 69 were committed against women, many of whom were candidates for public office, representing 13% of the violence. However, this should not be interpreted as women being less likely to be targeted. Despite the 2024 elections being notable for women’s candidacies for president, Claudia Sheinbaum’s subsequent victory, and the National Electoral Institute (INE) guidelines for parties to ensure gender parity in candidacies, there remains insufficient representation of women in local official bodies. In 2023, only 28% of local positions were held by women.19 In fact, female candidates received more threats than men during the 2024 electoral process,20 often forcing them to withdraw from the race, as was the case for 217 female candidates in Zacatecas alone.21

Pressure on Local Authorities Beyond Elections

Candidates were not the only political figures exposed to violence in the recent election cycle. Over 40% of the 540 incidents of violence targeted current and former officials not running for election, such as mayors and public servants. The persistence of violence against these officials indicates an intent to exert pressure on political processes beyond election periods.

ACLED data reveals that public officials across different sectors are affected. Officials dealing with judicial and security matters, and public administration treasurers were the most frequently targeted non-elected officials. This trend is largely attributed to organized crime groups’ interest in controlling local resources and key administrative areas, such as security and judicial functions, which can impact their operations. Indeed, non-running public officials are targeted nationwide, but they represent a larger proportion of victims in states severely affected by organized crime-related violence, such as Guanajuato, Guerrero, and Michoacán.

Family members of politicians were also among the victims in approximately 14% of attacks against politicians, either as direct targets or related casualties. Often, violence against family members reflects an attempt to exert pressure on a political figure. For instance, in October 2023, alleged members of the Jalisco New Generation Cartel (CJNG) attempted to kill the brother of the mayor of Tacámbaro—himself a former mayor—after the group issued threats against him and his treasurer. In at least 28% of these cases, targeted family members were also public officials or politicians, highlighting that a few families concentrate significant political power but are not spared from attacks, especially in states like Guerrero, Michoacán, and Puebla.

A notable example is the influential Salgado family in Guerrero state. Several members of the Salgado family hold elected positions and have also been targets of threats and attacks in recent years. In August 2023, Zulma Carvajal Salgado—cousin of the governor of Guerrero, Evelyn Salgado Pineda, who succeeded her father, Félix Salgado Macedonio—was victim of an attack that resulted in the death of her husband. The attack occurred shortly after she announced her intention to run in the municipal elections in Iguala.

Electoral Violence: A Cycle Beyond Campaigning

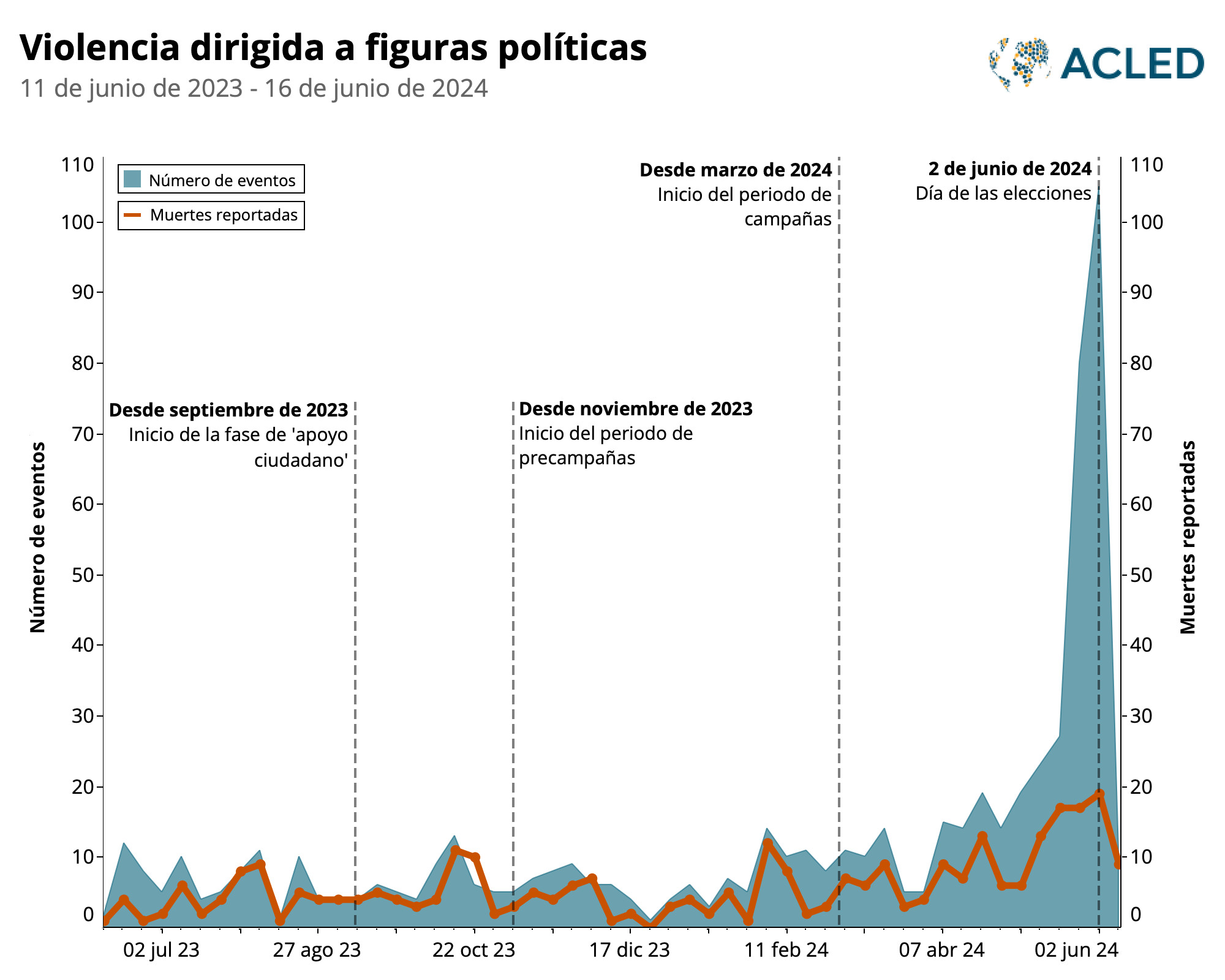

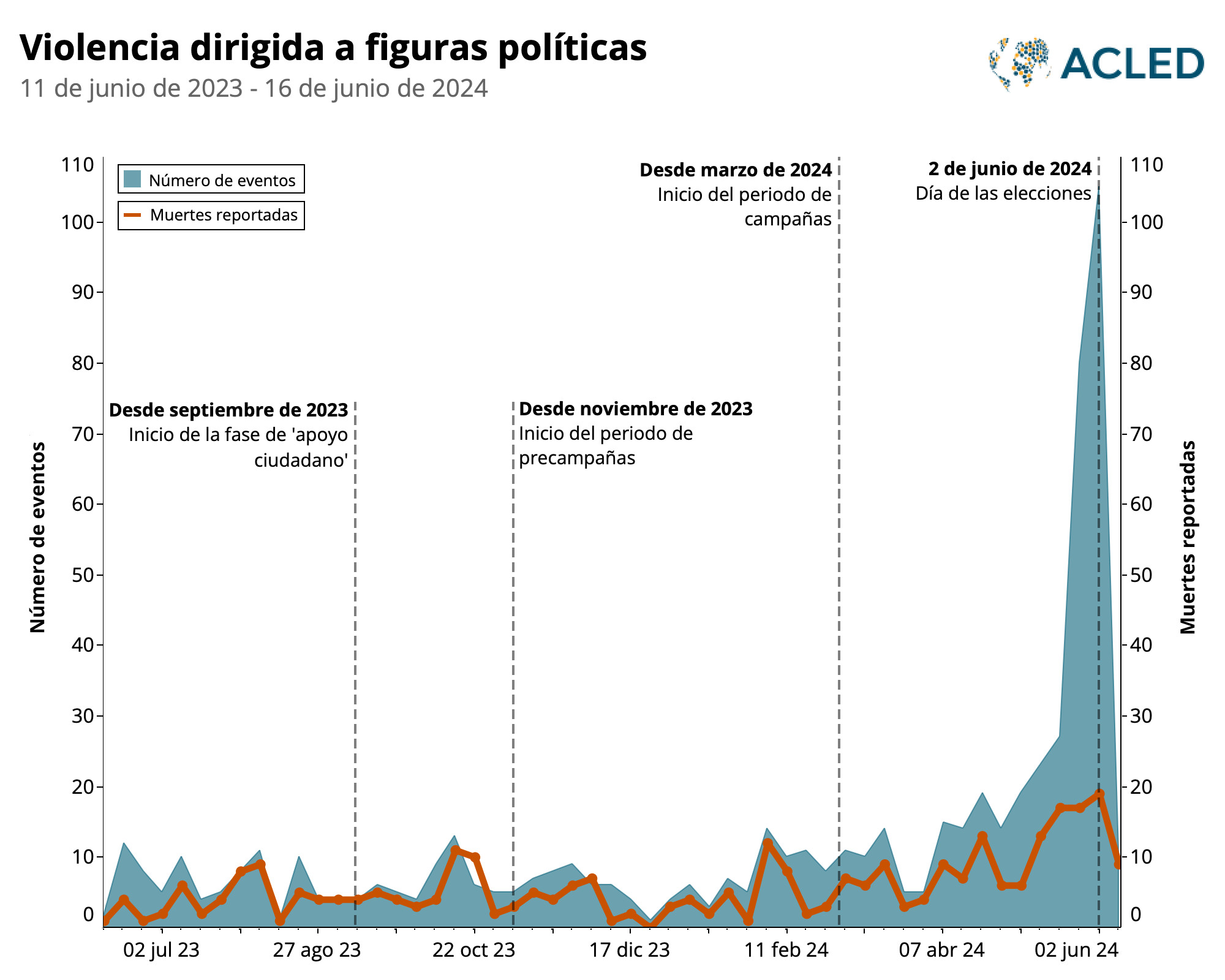

As in previous electoral processes, pre-election unrest, particularly violence against political figures, began to rise even before campaigns officially started. Violence against political figures experienced an initial spike in October 2023, shortly after the start of a period called citizen support, which began on September 9, 2023, in some states. During this period, aspiring candidates for president, senate, and federal councils gather signatures to run as independent candidates. After a relatively constant level between November 2023 and January 2024, violent events against political figures increased substantially in February (see chart below). This increase coincided with the end of the pre-campaign period in most states, when aspiring candidates from political parties conduct public activities to gather support for their nominations.

Violence targeting political figures in Mexican states between September 2023 and June 2024

Violence targeting political figures in Mexican states between September 2023 and June 2024

Violence against political figures occurring very early in the electoral cycle is often related to perpetrators’ intention to mark territory. A violent incident signals that the area is under their influence and aims to deter candidates they deem threatening or unaligned.22 The majority of victims in at least 34 events recorded in October 2023 were current or former local representatives and their family members, but some targeted elected positions. For example, on October 4th, the mayor of the Cuauhtémoc district of Mexico City, who was seeking to become a candidate for head of government of Mexico City for the Party of the Democratic Revolution, was attacked by a group of individuals while visiting the capital’s food supply center.

However, violence against political figures escalates once candidacies are defined, as those seeking to influence contests through violent means can more easily identify targets. From the start of the campaign for federal and state elections in March and local elections in April, violence against political figures increased exponentially, reaching a peak of 132 events in May, resulting in 55 fatalities and marking a record in both figures since ACLED began covering the country in 2018. Election Day itself experienced the highest number of events against political figures, with 80 events recorded.

Nevertheless, the risks for political figures are unlikely to cease after the elections. In Guanajuato, for instance, armed men attacked the business of the elected mayor of Tarimoro days after he won the election.23 Furthermore, previous election cycles suggest that violence will not only remain high at least until the inauguration ceremonies but will continue throughout the new administrations. ACLED recorded 210 and 179 events in the six months following the 2018 and 2021 elections, respectively, as well as consistent levels of violence over the years, totaling nearly 3,000 events of violence against political figures since ACLED began its coverage.

Organized Crime Competition Fuels Election-Related Violence

ACLED recorded high levels of violence against political figures in the states of Guanajuato and Michoacán, two of the federal entities most affected by organized crime violence in the year leading up to the 2024 vote, confirming that in some states, competition between criminal groups drives violence against political figures. Six of the ten states with the highest levels of incidents against political figures during the electoral cycle are also among the ten most affected by organized crime-related violence in the same period (see map below). This is particularly true for Guerrero, which ranks second in the number of violent incidents against political figures, but first in the number of fatalities in these attacks, and fifth for violence likely related to organized crime during the electoral cycle (see table below). In Chiapas, the state with the highest levels of violence against political figures during this election process, increased violence linked to the rivalry between CJNG and the Sinaloa cartel contributed to a more than 90% increase in violence against political figures compared to the 2021 election cycle. The high levels of violence led to the cancellation of voting in Chicomuselo and Pantelhó.24

Map of Mexican states showing levels of violence targeting political figures during the 2024 election cycle

Map of Mexican states showing levels of violence targeting political figures during the 2024 election cycle

However, there are some exceptions to this pattern, particularly when one organized crime group exerts hegemony. In fact, the states of Jalisco and Sinaloa are among the ten most affected by organized crime violence but are not among those with the most events of violence against political figures. They are also, respectively, the strongholds of the CJNG and the Sinaloa cartel, suggesting that their influence in local politics may be so extensive that they do not need to resort to violence against political figures to consolidate that influence.25; 26 Much of the violence recorded in those states, in fact, stems from these groups’ tactics to exert territorial control and may occasionally be related to localized disputes with smaller groups, such as violence involving the Nueva Plaza cartel in the Tlajomulco area.27

However, in some cases, the presence of a strong political establishment dominated by a few families also contributes to low levels of violence against political figures. Nuevo León is an example of this. Despite registering some of the highest levels of organized crime violence, violent incidents against political figures have remained limited in the past year. Nuevo León is the second wealthiest state in the country, with an economy led by export-oriented manufacturing. A small number of families concentrate most of the wealth and political power. The main candidates for governor in the 2021 elections, some of whom are part of these families, have been accused of links to criminal organizations such as Los Zetas and the Gulf Cartel (CDG).28 Furthermore, since the collapse of the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) hegemony in the 1990s, the state has been governed by the Citizen Movement or independent candidates, but MORENA has failed to make significant inroads into the state’s political sphere.29 In the recent elections, in fact, it only won two of the state’s 51 municipalities.30

Local Power Struggles: Another Key Driver of Violence

Beyond direct attacks against political figures, a significant portion—30%—of incidents manifested as riots and property destruction. These events were linked to expressions of public discontent towards local representatives or rivalries between competing political actors. They were particularly prominent in Chiapas, Puebla, and Hidalgo (see chart below). These three states are more susceptible to local power struggles and electoral disputes due to pre-existing inter-community conflicts and the concentration of power in the hands of local power brokers or caciques.

Before election campaigns began, this form of violence primarily erupted during protests in which demonstrators confronted representatives for failing to fulfill their demands. However, property destruction and collective violence can also be used by political contenders to intimidate their adversaries. Indeed, these events increased notably during the election campaign in April and May and included attacks against candidates’ and officials’ properties and collective actions against supporters of a rival faction. For example, on May 15th, in Tlanchinol, Hidalgo, armed men shot at a vehicle parked in front of the house of a candidate seeking to join the municipal council for the MORENA-PANAL alliance, who had already reported receiving threats before the election.

Finally, disturbances surrounding election day are often related to the rejection of results or allegations of irregularities or vote-buying during the process by a candidate. For example, on June 1st, in Puebla, a group of 200 people, including supporters of the PRI and the National Action Party (PAN), physically assaulted MORENA members in Venustiano Carranza over alleged vote-buying. Due to the incident, the State Electoral Institute decided to annul the election results due to irregularities.31 Similarly, in Chenalhó, Chiapas, supporters of the Green Party of Mexico clashed during an assembly to elect their representatives amid accusations that the disturbances were orchestrated by the mayor to prevent his candidate from losing.